Do you have an artist at home? Your child may love to doodle during their free time, or maybe your child has a passion for art! No matter what you are looking for, giving your child easy drawing prompts can simultaneously help them grow their love and skill. So, if you're asking yourself, what are some easy things my child can draw? You have come to the right place! Here are some very simple yet fun things your child can draw today.

Key Points

- Kids can learn attention to detail and how to explore their creativity through drawing!

- Your child will develop their cognitive ability and fine motor skills through drawing.

- Fruit and animals are just a couple of things that your child can enjoy drawing!

Benefits of Drawing For Kids

Drawing has many benefits for kids and adults, whether your child has a natural talent or just loves to draw.

Increases Autonomy for Kids

Putting a pencil in a child's hands and asking them to draw what they see in their mind can help increase their sense of autonomy. Every child needs to feel the ability to make their own choices. This is what autonomy is. Giving your child opportunities to explore their independence is important as parents. You can do this even with something as simple as drawing!

Increases Skill in an Easy Way

Does your child have a natural talent? They may have a passion for drawing and want to improve their skill. Whatever the case, your child increases their drawing skill every time they pick up a pencil. Talent only improves drastically over time. Taking small steps is important for helping your child grow their skills. If your child becomes frustrated because they aren't improving fast enough, you can encourage them in a few simple ways:

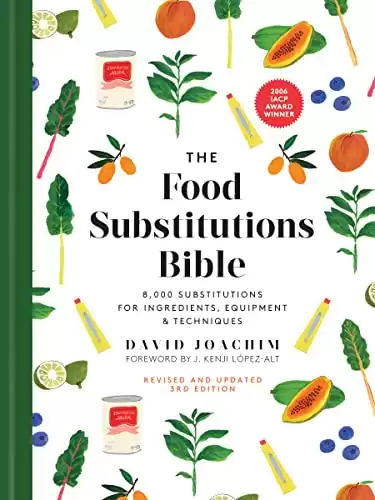

- The must-have convenient reference guide for every home cook!

- Includes more than 8,000 substitutions for ingredients, cookware, and techniques.

- Save time and money on by avoiding trips to grab that "missing" ingredient you don't really need.

- Encourage taking breaks.

- Focus on something other than the current task.

- Remind your child of the progress they have made.

- Take baby steps with the drawing.

- Praise the improvement you have noticed in your child's skill.

- Remind your child that Rome wasn't built in a day.

- Look back at other skills that they have made progress in.

- Introduce your child to someone who has improved on the skills they desire.

Attention to Detail through Drawing

Drawing will help your child learn to pay attention to detail. Have you ever asked your child to do something and then realized they were not paying attention to the details of what you were saying? Attention to detail is a learned skill; children are not born with it. That is why practicing anything requiring attention to detail is an excellent way to improve this skill.

Kids Can Learn New Concepts

The possibilities when it comes to art are endless! Art can be whatever your child wants it to be. They may enjoy drawing rainbows or hearts, or maybe details on faces are more their thing. Drawing gives your child the room and ability to learn and develop new concepts and skills. You should encourage them to challenge themselves with new ideas and new types of drawings. You can even buy them a how-to-draw book to help them learn how to draw new things!

Expresses Creativity in an Easy and Fun Way

Art is an excellent and easy way to express creativity! Every kid is creative. They just need to hone in on their specific creative skills. Having your child grab a piece of paper and focus their creativity on something that was initially blank will help them express creativity. You know what they say, creativity begets creativity! So the more your child expresses their imagination and creates, the more creative they will feel!

Improves Concentration through Drawing

Concentration is needed in almost anything your kids do, whether it is a sport, school, reading, or even focusing on a fun game! Concentration is a great skill to sharpen, and drawing will help your child improve. They will have to sit still and focus on an easy drawing of what they see in their mind's eye. This takes concentration!

Develops Fine Motor Skills

Fine motor skills are needed in everyday life. Drawing is a great way to focus on developing fine motor skills. The skills it takes to hold and grip a pencil are developed over time by repetition. So when your child works their fingers and manipulates their hands in a way that makes them work those muscles, it will help them develop fine motor skills.

Encourages Cognitive Skills

Concentration, fine motor skills, and creativity are all cognitive skills that children need as they grow. Drawing will help encourage these mental skills and more! Having well-developed cognitive skills will help a child excel in school and stay on pace with their peers.

Increases Ability to Plan through Drawing

When your child sits down to draw, they need to plan out, whether on paper or in their head, what they want to draw! Some people naturally have planning skills. Others do not. But the ability to increase planning skills is something that can be learned. Drawing helps your child improve their planning skills by putting them into practice.

Increases Their Self-Esteem in an Easy and Fun Way

Everyone loves to be proud of the work they have done. Children are no different. When your child draws something they are proud of, you can help encourage their self-esteem too! Hang the drawing somewhere you can see it. A child's sense of pride in seeing their artwork displayed is priceless.

Easy Things for Kids to Draw

Cloud and Rainbows

Clouds and rainbows are some of the easiest shapes to draw. The rainbows take just straight lines, and the clouds squiggly lines, making this a drawing that can be shaped and created in many different ways! So have fun with this one, and add different colors.

©

Flowers

Flowers are some of the first things kids learn to draw. The circle is a staple making this one of the easiest drawings a kid can do. Your child can pick different colors for each flower, different arrangements and shapes for the petals, and even different types of flowers!

- The must-have convenient reference guide for every home cook!

- Includes more than 8,000 substitutions for ingredients, cookware, and techniques.

- Save time and money on by avoiding trips to grab that "missing" ingredient you don't really need.

Hand Animals

Using your hands to draw an animal is easy and fun. All you need to do is trace your hand and maybe even your arm. Then, add your colors and face! There are a lot of animals that can be drawn with a hand, so encourage your child to be creative! If they aren't sure where to start, a hand turkey is always a go-to.

Animal Faces

Animal faces all start with the same thing, whether your child is drawing a cat, a dog, or a bunny. They start with a circle. Work on their fine motor skills by having your child draw a circle. Then fill it in with any animal they want! Cats and dogs are a kid's favorite.

Fruit

Fruit is so fun to draw! For example, a strawberry can be drawn as a heart, or a pear can be drawn as an upside-down diamond. The possibilities are endless! You can use this as an opportunity to teach your child about the different kinds of fruit.

Tacos

A taco can be fun to draw because you can use your imagination and add whatever you want! Start by drawing a line. Then begin at one end of the taco and draw upward, making a half-circle. Stop before you connect the lines, continue up, and create the other side of the taco. Decorate and fill the inside of your taco with any ingredients you want!

Popsicles

Who doesn't love popsicles to eat? Well, drawing them is just as fun! Drawing a popsicle is very simple. Outline the popsicle, add a stick, and any other details you want. It is that easy.

©

Pumpkin

Pumpkins are fun to draw because of the ability to create any face in your jack-o-lantern! These cute pumpkins are fun to create in the fall, but they can be enjoyed any time of the year. If your child is too young to participate in pumpkin carving, this can be a great way to help them feel included.

Turtle

Turtles are probably one of the easiest animals to draw. That is because the shell is a circle. Add the head at the top and the legs, arms, and tail. You can make your turtle unique by adding any design you like!

Ladybug

A ladybug is just as easy as a turtle. Draw a circle, leaving a small slit at the bottom. Add a half circle for the head. Color your ladybug red and add black dots. Remember the legs and the antennae. Your ladybug is now ready to go.

Pineapple

Draw an oblong circle. After you draw the circle, start on the leafy top by adding two leaves at the bottom and another on top, and continue until you are happy. Next, add crisscross lines, and then you are done. You have a super cute pineapple!

Watermelon

Drawing a watermelon can be so easy! Draw half a circle. Then draw another line on the inside. You can stop there, add seeds, and color the watermelon red and green. Additionally, you can take it a step further and add a cute face! The possibilities are endless.

In Conclusion

Drawing has many benefits for children. It increases creativity, passion, and concentration. There are so many cute things that children can draw! If your child loves animals, have them try their hand at animal faces, a turtle, or even a hand animal. Maybe your child loves food. Tacos, strawberries, or pumpkins are perfect for trying. Have fun and get creative with these super fun ideas.

The image featured at the top of this post is ©Weseeel/Shutterstock.com.

- The must-have convenient reference guide for every home cook!

- Includes more than 8,000 substitutions for ingredients, cookware, and techniques.

- Save time and money on by avoiding trips to grab that "missing" ingredient you don't really need.