San Francisco is a city filled to the brim with fun things to do in the summer. The best camps in San Francisco offer children a chance to build new skills, learn new interests, and make new friends. San Francisco has more than enough attractions on its own, when it comes to finding summer camps around the city, there are so many options to pick from. If you’re wondering where to look, check out some of the many arts, STEM, and outdoor camps available in the bay. If you’re looking for outside-the-box options, there’s a spy camp and a woodworking camp that accept kids of all ages. Or maybe a sports camp is the summer fun your child is looking for. San Francisco’s got it all and more. Keep on reading to learn more about some options to fill your child’s summer with fun and new experiences.

Arts and Crafts Summer Camps

The San Francisco art scene is strong when it comes to summer camps. Check out the many music, crafts, and dance camps available to children of all ages. Arts camps that are centered around new experiences can bring so much to your child’s life. Perhaps they’ll find a passion for woodworking, theater, or painting. And, of course, what is summer camp without making some new, great friends along the way?

Murphy Music Camps

The Murphy Music Camp is one of the top camp options in San Francisco for summer music education. Send your children to work with professional musicians who will guide your children in music creation and learning. Pick from band camp, orchestra camp, digital music video camp, or choir camp. Take classes and work on projects. At the end of camp, every camper will take part in a showcase that parents can attend to see the musical strides their child took this summer!

Space M Academy

At the Space M Academy, campers have their pick of summer or winter session. Camp at this center in San Francisco includes the option of a couple of different artistic avenues. Your child will be able to take courses in creative art, air clay, or focus their summer classes on a particular instrument. Sign your young artist up for quality time learning from qualified staff and fellow creatives. They'll hone their artistic skills and make some interesting friends and lovely memories along the way.

©LightField Studios/Shutterstock.com

Petit Pas Studio

For all your dance and theater camp needs, check out Petit Pas. With five available summer camp sessions, you can take your pick of the theme that fits your child. Check out themes like safari, magical powers, space and ocean adventures, and many, many more. A day at camp includes dance, yoga, theater games, acrobatics, crafts, and lessons in French. Day camps are open for 5-10-year-olds and last from 9 am-3 pm with the option for extended care if needed. Afternoon snacks will be provided as part of the Petit Pas camp package!

The Butterfly Joint

For an interesting summer camp experience, why not sign your child up for some woodworking? At The Butterfly Joint Summer Camps, children entering Kindergarten and up can take courses and learn the craft. Camps run from 9 am-3 pm with lots of time spent outdoors and snacktime provided during camp hours. Outdoor time is held in locations local to San Francisco, Sutro Heights Park, Golden Gate Park, or even at Ocean Beach! Your child will learn some new skills, make some new friends and get to spend their summer in a fun and creative environment.

Canvas Dance Arts

The Canvas Dance Arts Summer Camp offers classes at two different studios in the city. Children have the option of participating in the one-week session or the full five-week sessions! Taught by Ms. Simone and Miss Angela, young dancers will work on strength conditioning, creativity, and choreography as well. Your blossoming artist will come away from this summer camp with newfound confidence as a dancer and performer. Enjoy a final video of the performance as a forever keepsake of this summer.

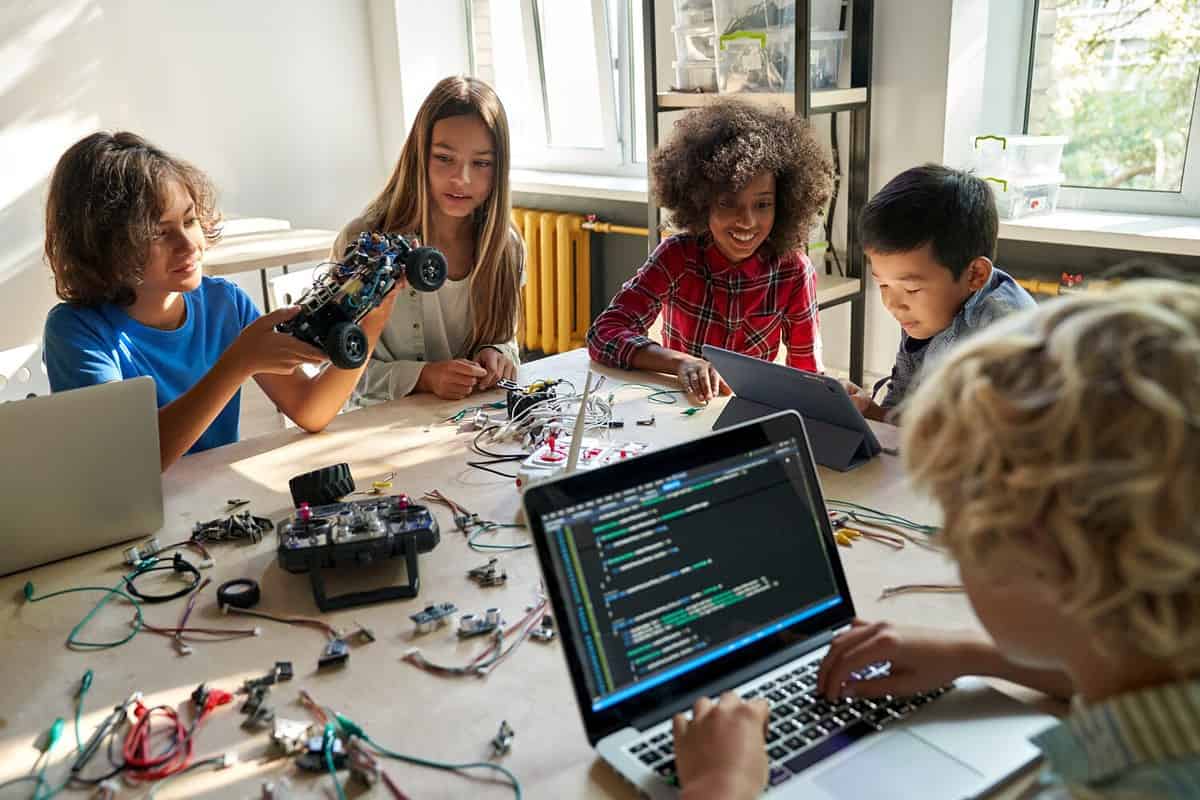

Science and Discovery Camps

How does a summer of learning sound? And what if it came along with loads of fun at an educational summer camp full of like-minded kids? From STEM camps to tinkering schools, there are many avenues for your child to explore this summer. Read on to learn more about the programs available within the San Francisco City limits.

Galileo Camps

At Camp Galileo, children are encouraged to innovate and experiment. At this camp, counselors, teachers, and staffers work together to foster an environment of fun and learning. Pick the session that best fits your child, with three options open to K-8th graders. Your child will participate in hands-on innovation exercises, STEAM projects, and lots of outdoor fun and learning time. Parents rave about this camp as one of the best camps in San Francisco.

SF STEMful

STEMful, a STEAM center based in San Francisco, hosts camps and programs for children as young as 1.5 til age 10. Summer camps are open to ages 3.5-9.5 and encompass all kinds of hands-on learning and STEAM-related educational fun. Your child will spend their summer building new interests in areas that could truly lead to a future career path. And they'll make lots of new friends along the way

©Ground Picture/Shutterstock.com

Spy Camp

Curiosity should be nurtured, and what better place to learn than at Spy Camp? Through the arts, outdoor training, STEM labs, and more, Spy Camp helps children to build skills that can be applied in the real world with a backdrop of fun and espionage. There is a two-week session and a one-week session available depending on your family's summer schedule. Open to children ages 6.5-10 years old.

Outdoors and Athletics Camps

Outdoor camp opportunities can be such a great way to spend the summer. Or maybe getting some training in before the next season of sports is the place for your child to be. There’s even the opportunity to paddle out onto the beauty of the bay. Active summer camps can be such a great option for a fun summer experience and a great energy outlet. Check out some of the best camps in San Francisco for those energized kiddos looking for some summer fun.

SF City Kid Camp

At the City Kid Camp of San Francisco, children ages 8-12 will get to know the great outdoor spaces of their city. With a focus on youth development, campers will participate in daily games and different sports. These activities are combined with lots of fun learning about the natural environment and the history of San Francisco. Fostering awareness in a safe, fun, space, this camp is a great way to connect your children to their city and the beautiful nature within it.

©https://www.shutterstock.com/g/robertkneschke/Shutterstock.com

Dog Patch Paddle

At Dog Patch Paddle, kids ages 7-14 will get the chance to get out on the water. They'll learn how to handle themselves on paddle boards, canoes, kayaks, and more. With sessions based on experience and skill level, campers will get to go on day-long excursions and learn about the wonders of water safety. Send your children out to learn a new skill and have some summer fun!

Urban School Athletics

There are lots of athletics summer camps around the San Francisco bay area. This one caters to Basketball specifically. At the Urban School Athletics Camp, young athletes will work on their shooting, dribbling, and offensive and defensive footwork. Under the guidance of Coach Joe Skiffer and the talented players of Urban’s Blues NCS championship basketball team, campers in 5th-8th grade will have a great time at this summer camp!

The image featured at the top of this post is ©lunamarina/Shutterstock.com.