It may be common knowledge to find out how much something weighs, you put it on a scale. We weigh everything to determine weight, from food to cars to furniture to people. In fact, for people, getting weighed is part of life. From the moment we are born, and at every doctor's appointment, we step on the scale to see how much we weigh. Yet, weight isn't always a determining factor in our health. Which is where the BMI chart steps in.

To get an accurate health reading, doctors focus more on a person's Body Mass Index, a term first used in the mid-19th century, although it wasn't until 1972 when Physiologist Ancel Keys gave it a modern name and coined the acronym BMI. Body Mass Index (BMI) is a widely used measure by healthcare providers, researchers, and fitness experts to assess an individual's overall health.

BMI serves as a screening tool to indicate potential health risks but is not designed to diagnose an individual’s overall health and has been criticized for not being accurate in the past. For example, someone who has low fat but excess muscle can have a skewed BMI.

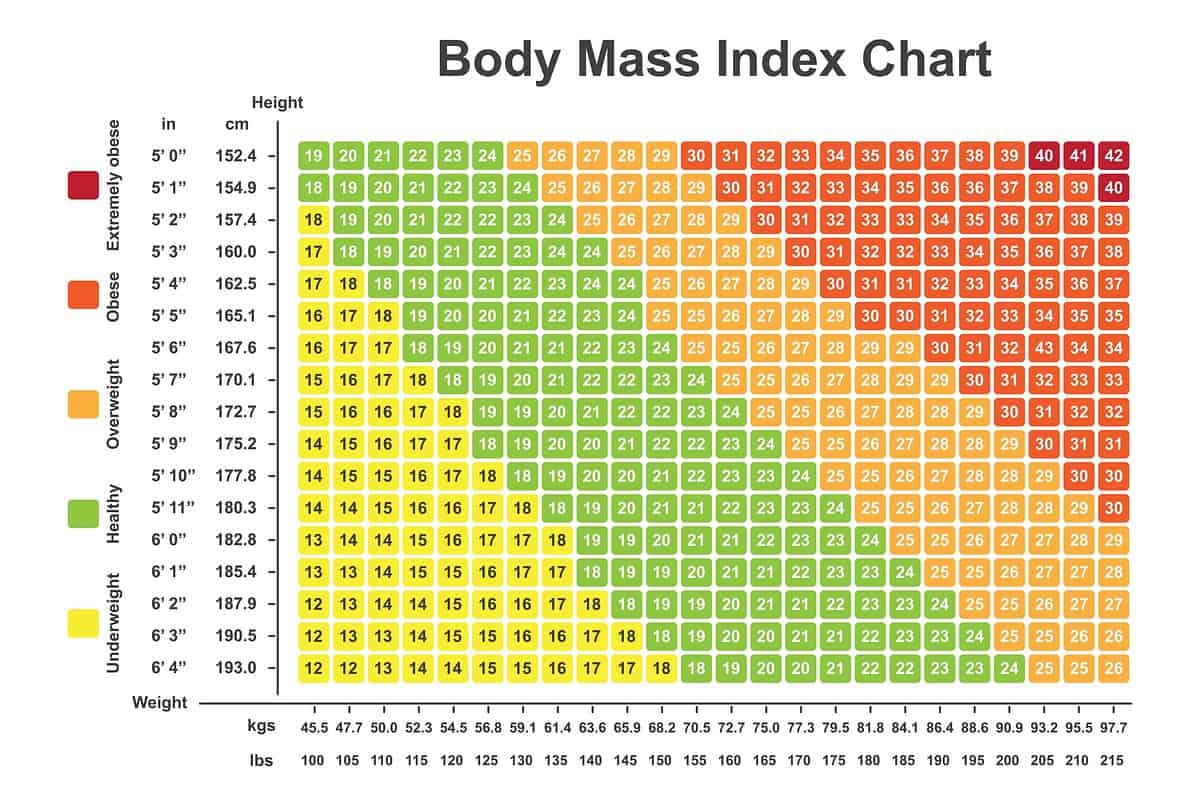

Based on the BMI chart below, you can calculate your BMI to see if it indicates you are underweight, a healthy weight, overweight, or obese. If you score below 18.5, then your BMI is underweight. A healthy weight is between 18.5 and 24.9. 25 to 29.9 is considered overweight. Anything over 30 is obese. Once you know your BMI score, keep reading to learn more about your BMI.

©Ali DM / Shutterstock/Shutterstock.com

Underweight

Although most people think health risks only come with being overweight or obese, this is also true for being underweight. If you're underweight, your doctor will likely help you come up with a plan to gain weight. Health risks from being underweight include osteoporosis, anemia, weakened immune system, fatigue, and irregular periods.

Healthy Weight

Maintaining a healthy weight is best for you. It allows your body to function as needed. Staying a healthy weight can reduce your risk of diabetes, heart disease, stroke, high blood pressure, cholesterol, and cancer. To maintain a weight in this category, make sure to continue eating the right amount of calories and get regular exercise.

Overweight

If your BMI is in the overweight category, then you should consider what needs to be done for you to get into the healthy weight category instead of increasing your BMI to the obese category. Reducing your daily caloric intake and incorporating some exercise into your routine will be pivotal to reducing your BMI.

Obese

If your BMI is 30 or above, it is considered to be in the obese category. If, after testing, it is true that you are obese, your doctor will likely speak with you about a plan to lose weight. Being obese is known to increase health risks and diseases. Some of these include high blood pressure, high cholesterol, type 2 diabetes, heart disease, stroke, osteoarthritis, sleep apnea, cancer, body pain, and mental illness.

The image featured at the top of this post is ©vadimguzhva / Getty Images.