Most Americans Can't Answer These US Geography Questions

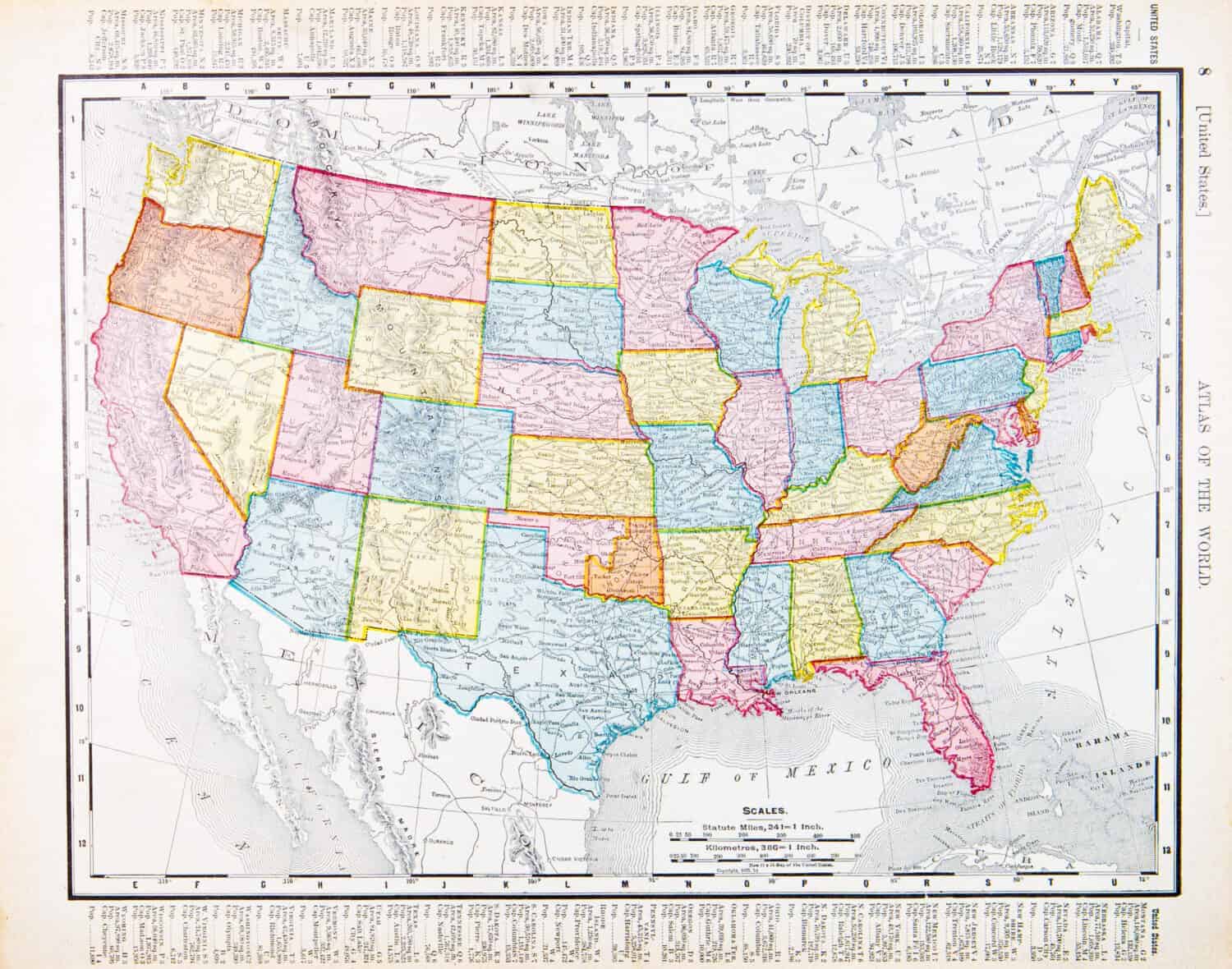

When it comes to trivia, certain facts are thought of as common knowledge. No matter the subject—especially when it concerns our own country—there are fundamental facts we’re taught in school or as citizens that we really ought to know. Especially when it comes to U.S. geography. We all know that the United States is comprised of 50 states, plus the District of Columbia, that Rhode Island is the smallest state, and that the country is bordered by Canada to the North and Mexico to the South. Or do we?

It may come as a surprise to know that many questions we think of as basic U.S. geography that everyone knows, or should know, most Americans get wrong. And those states mentioned earlier? Some don't even know exactly how many states there are. Take this U.S. geography quiz to see how you fare against the rest of the population.

Question

What is the largest freshwater lake not only in the U.S. but the world by surface area?

Answer: Lake Superior

Lake Superior covers approximately 31,700 square miles.

Question

What is the only state in the U.S. that shares its border with only one other state?

Answer: Maine

The only state that Maine shares its border with is New Hampshire.

Question

Why is Great Salt Lake in Utah salty?

Answer: No Outlet

Utah's Great Salt Lake is salty because there are no outlets. Its tributaries deliver small amounts of salt, and once that water reachest the lake, it evaporates, leaving the salt behind.

Question

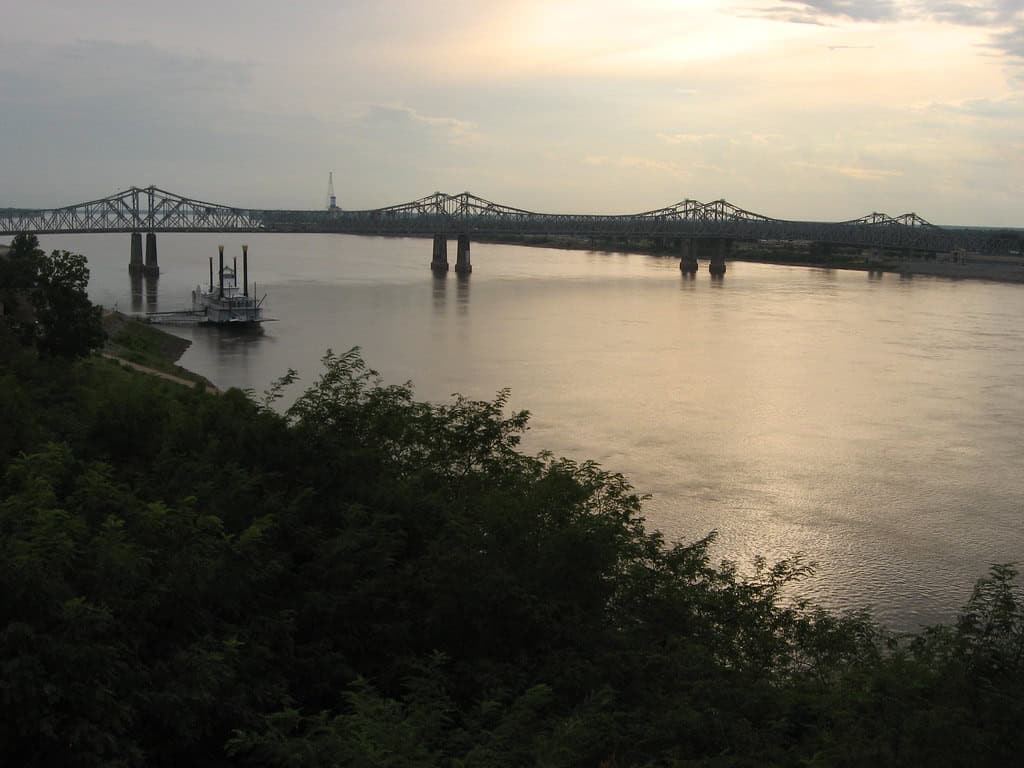

Which river flows through more states than any other U.S. river, and how many states does it flow through?

Answer: The Mississippi River

The Mighty Mississippi flows through 10 states, including Minnesota, Wisconsin, Iowa, Illinois, Missouri, Kentucky, Tennessee, Arkansas, Mississippi and Louisiana.

Question

What is the most densely populated state in the nation?

Answer: New Jersey

New Jersey covers 8,723 square miles and has a population of 9.6 million people. That makes it the most densely populated state in the nation, with 1,259 people per square mile.

Question

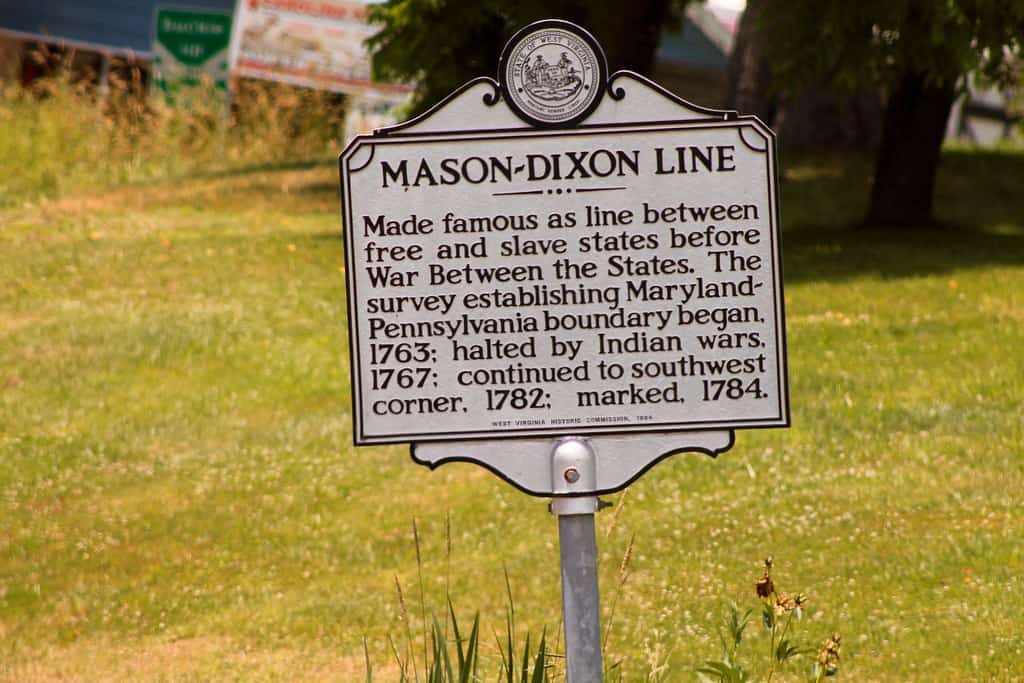

What is the Mason-Dixon Line?

Answer: A Land Dispute Resolution

While many Americans simplify the purpose of the Mason-Dixon Line as separating the north from the south, its original purpose was to resolve a border dispute between the British colonies of Pennsylvania and Maryland. It is named after the land surveyors, Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon and in pre-Civil War times, it was the line dividing slate states of the south and "free-soil" states of the north.

Question

How long is the Appalachian Trail, and where does it start and end?

Answer

The Appalachian Trail is 2,190 miles. It stretches from Katahdin, Maine to Springer Mountain, GA. FUN FACT: Tara Dower just beat the record for fastest time completing the thru-hike of the Appalachian Trail. She did it in 40 days, 18 hours and 6 minutes. The average hiker takes 5-7 months to complete the journey.

Question

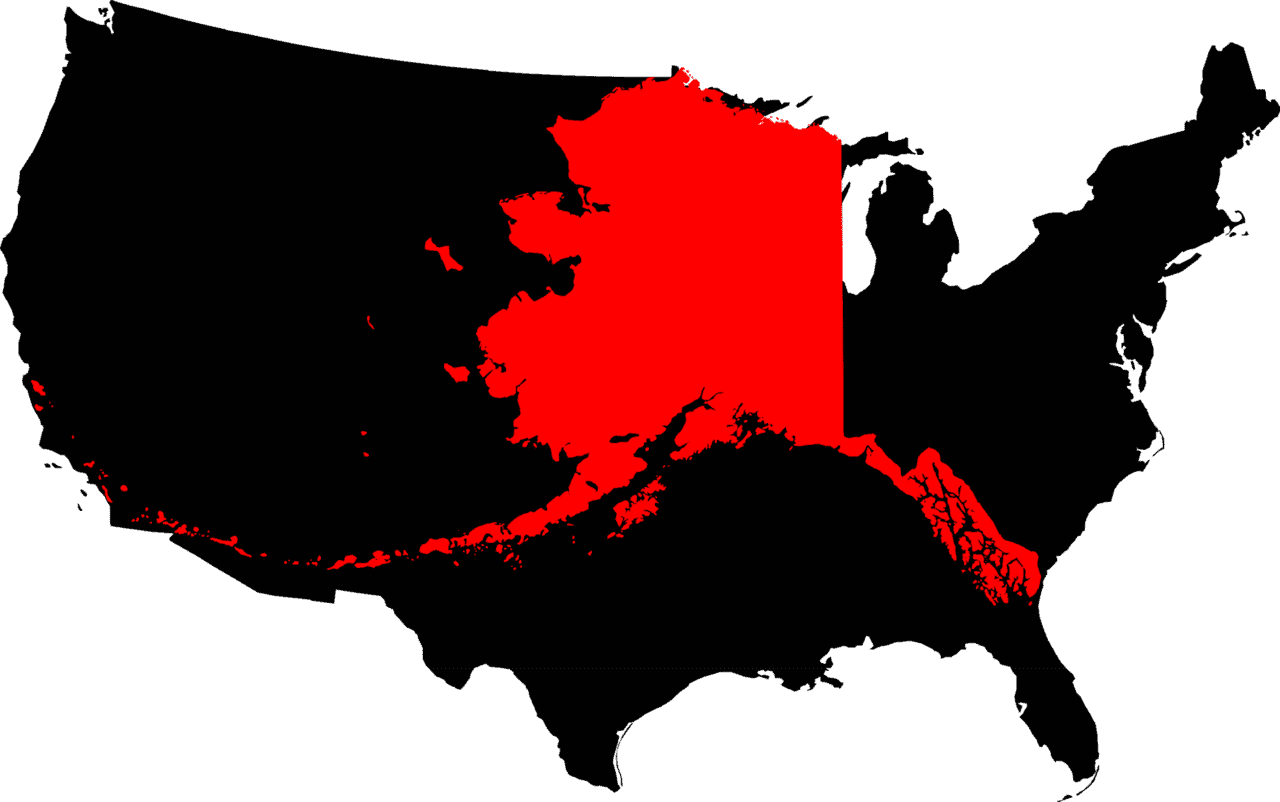

Where is the longest coastline in the United States?

Answer: Alaska

Alaska holds the title of the longest U.S. coastline. It spans 6,640 miles along the Pacific Ocean.

Question

What is the lowest point in the United States?

Answer: Death Valley

Death Valley is located at -279 feet below sea level, making it the lowest point in the United States. It also receives the least amount of rain.

Question

What is the highest point in the United States?

Answer: Denali

The highest point in the United States is Denali in Alaska, which measures 20,310 feet above sea level.

Question

What are the smallest and the largest states?

Answer: Rhode Island and Alaska

Rhode Island measures 1,545 square miles while Alaska clocks in at 663,268 square miles.