Neglected Car Maintenance Habits That Can Lead to Trouble

Many of us rely on our vehicles without giving much thought to their upkeep, expecting them to start and run smoothly every day. However, keeping a car in top condition requires more than just refueling -- it demands regular maintenance. While some tasks are simple and quick, they're often overlooked, leading to potential issues down the road. Unfortunately, many Americans neglect these basic car maintenance steps.

Do you? If so, this guide will provide essential information that you should consider before you get behind the wheel again. These are also great life skills for children.

Q.) What Should You Replace to Keep Your Engine On Time?

This is one of the simple car maintenance tasks that's best done by a mechanic.

A.) The Timing Belts

When you go to the mechanic, ask them to check your timing belts. They ensure that your engine runs properly. If you forget, the belt could tear and break other components under your hood.

Q.) What Should You Change So Your Engine Doesn't Fail?

This is one of the most essential car maintenance tasks that everyone must do.

A.) The Oil

Do not put off changing your oil or it could be catastrophic. Oil is necessary for the performance of your vehicle. If you don't have lubrication in your engine, it could fail. The cost of a new engine is huge.

Q.) What Should You Rotate Regularly?

This is another one of the simple car maintenance tasks that's easy, but most people put off.

A.) Rotate Your Tires

Rotate your tires once or twice per year to ensure that they don't wear down. If you don't replace them, your car could start vibrating or the tires could wear out completely.

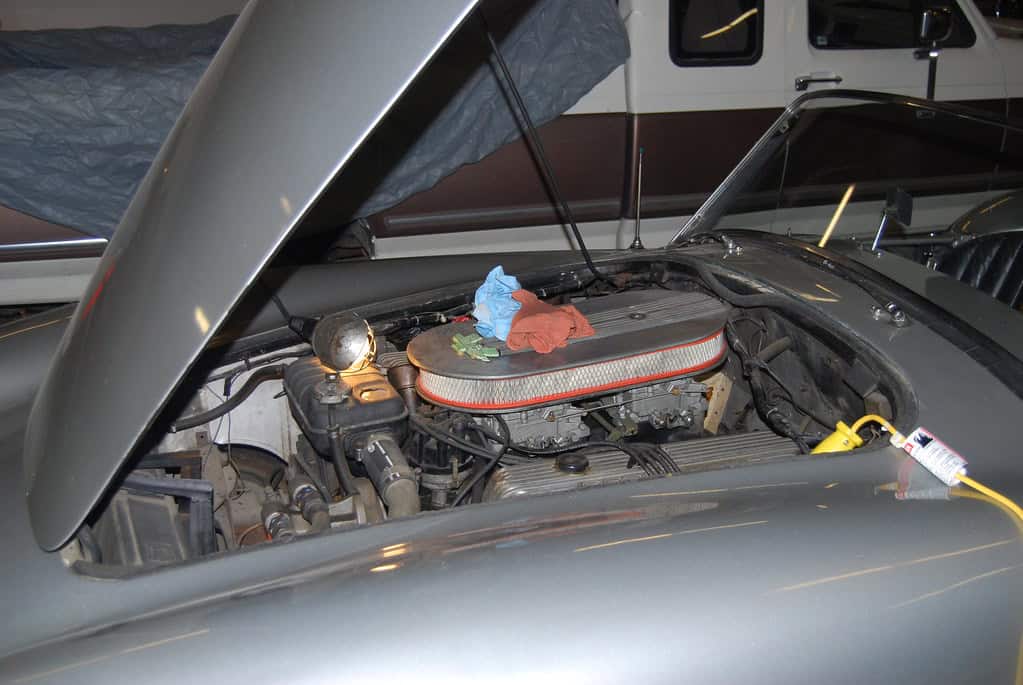

Q.) What Filters Should be Changed?

This is one of the most forgotten tasks.

A.) Change Your Air Filters

You should change your air filters at the intervals recommended by your vehicle's manual. Failure to change air filters can reduce engine performance. Plus, you'll likely get fewer miles per gallon.

Q.) What Should You Change So Your Car Stops?

Many people take the fact that their vehicle will stop for granted. What should you do?

A.) Your Brakes

Have your brakes checked whenever you go in for maintenance. If you hear your brakes grinding when you stop, then have them checked at your nearest convenience. You don't want your brakes going out.

Q.) Which System Should You Flush Annually?

This is one of the simple car maintenance tasks that a mechanic can do.

A.) Flush Your Cooling System

This is one that many people don't think about. However, you should flush your cooling system to avoid rust and debris build-up. You'll keep your engine running smoothly.

Q.) Changing This Fluid Will Help Your Transmission. What is it?

Many people forget the transmission.

A.) Transmission Fluid

Check your car owner's manual for when to change your transmission fluid. Old fluid can cause your vehicle to overheat, and shifting can become more difficult.

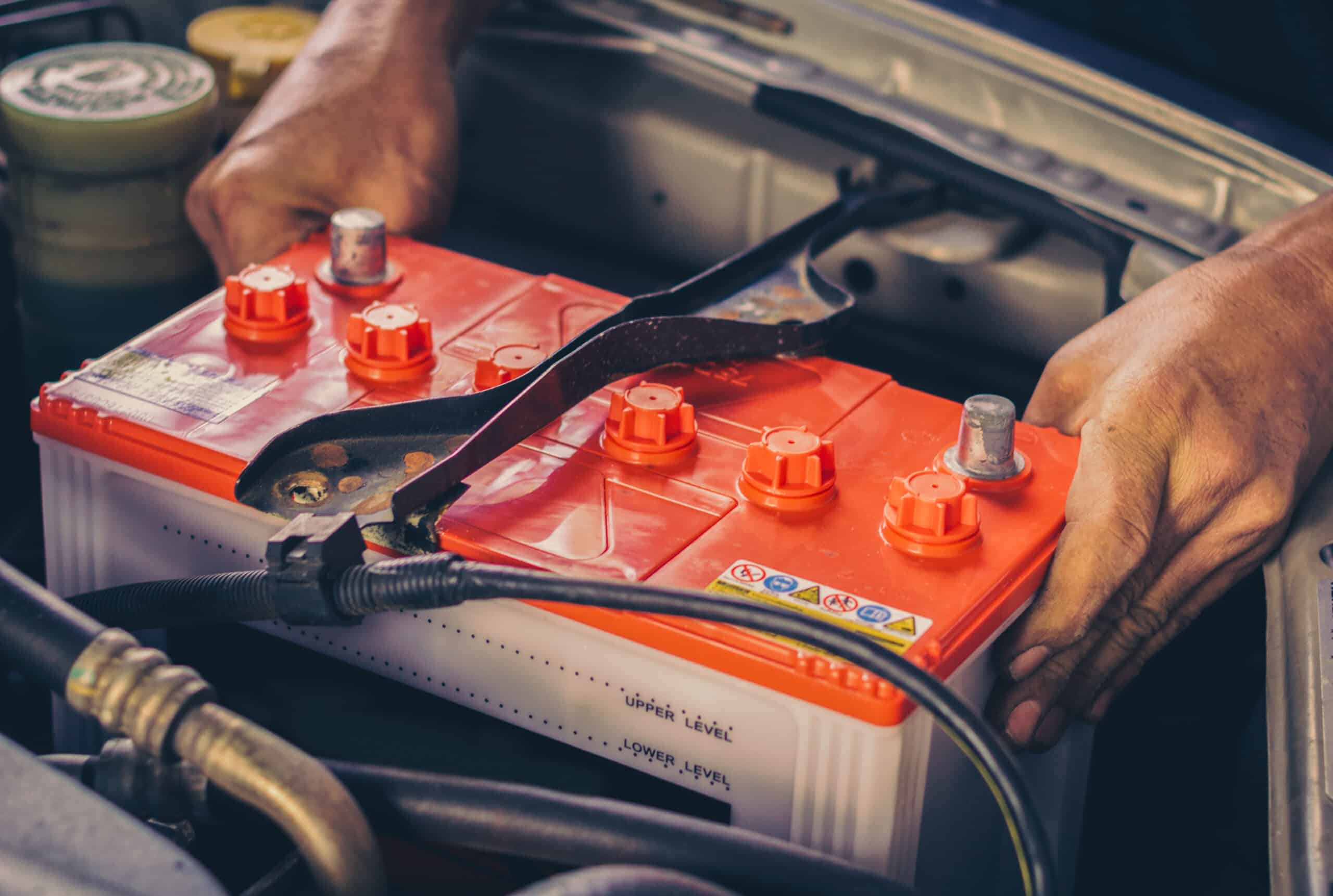

Q.) Cleaning This Item Under the Hood Will Help

The main piece that enables your car to turn must be maintained.

A.) The Car Battery

One of the simple car maintenance tasks you'll want to do is to clean your battery. More specifically, clean the battery terminals if you notice corrosion.

Q.) You Should Do This at the Gas Station. What is it?

Not every time, but occasionally.

A.) Check Tire Pressure

At least once per month, check the tire pressure when you stop for gas. Check the side of your tire for the necessary PSI, and don't fill it more than that.

Q.) What Should You Replace So You Can See?

They sure help when it starts raining!

A.) Your Windshield Wipers

Once you notice that your windshield wipers aren't working properly and are streaking, consider changing them. The last thing you need is for them to fail when the next major storm comes around.

Q.) There are Several of These Around the Vehicle That You Should Check. What are They?

This is perhaps the easiest of the simple car maintenance tasks.

A.) Check Your Lights

Take the time on a regular basis to check all of the lights on your car to ensure that they're illuminating and working properly. That includes headlights, hazard lights, brake lights, and turn signals.

Q.) Do You Regularly Use These Safety Mechanisms?

If you don't, you should.

A.) They are Your Seatbelts

Regularly check your seatbelts in front and back and ensure that they buckle properly.

Q.) How Can You Clean the Air in the Car?

This task is often missed.

A.) By Replacing Your Cabin Air Filter

You may not realize it but the cabin air filter is what is responsible for filtering the pollen and dust out of the inside of your car. It can get in through your ventilation system. Replace it so you can be healthy while you drive.

Q.) Did You Remember the Break Fluid?

There's more to checking brakes than just waiting to hear them grind.

A.) Refill Your Brake Fluid

The brake fluid is what helps your brakes to stop the car as smoothly as possible. Over time, the fluid can evaporate, so you need to replace it.

Q.) How Can You Make Your Fuel Work Better for You?

There's more to gas than just putting fuel in the car.

A.) By Cleaning Out Your Fuel System

Clean out your fuel system every 30,000 miles. A mechanic can tell you what's best for your particular vehicle. By doing so, you'll remove the gunk from your fuel injectors, and your car will accelerate much more smoothly.

Q.) How Do You Maintain Your Transmission?

The transmission is another essential component of your vehicle.

A.) By Replacing Your Transmission Fluid

Check under the hood and replace your transmission fluid when necessary. The fluid is responsible for lubricating your gears. Let it dry up and you could have big problems. Do this every 100,000 miles.

Q.) Do You Know Why Turning Your Steering Wheel is So Easy?

Yes, there's more to it than just turning a wheel.

A.) It's Because of Your Power Steering

Without power steering, turning the wheel of your car would be next to impossible, especially if you needed to turn quickly. Replace the power steering fluid so you're never faced with difficult driving.

Q.) How Do You Maintain Your Rear Wheels?

Cars are more complicated than you think!

A.) By Maintaining Your Differential

The differential of your vehicle is the gearbox at the rear of your vehicle that helps to propel your car forward. This is a part that you should have inspected after 60,000 miles. It's probably in fine shape, but it's better to be safe than sorry.

Q.) How Often Should You Change Your Car Battery?

Yes, it will need to be replaced at some point.

A.) Every 4-5 Years

By the end of 5 years, your battery will likely need to be replaced. If you don't replace it, one day you'll walk out to your car, and it won't turn on. Replacing the battery is a very easy process.

Q.) What Do You Do When A "Check Engine Light" Comes On?

This is one of the most simple car maintenance tasks you can do.

A.) Have Your Vehicle Inspected

It can be scary when a light turns on on your dashboard, but don't ignore it. It can mean something minor, or it could be a big deal. Have the car inspected just in case.