Discover the Charm of Arkansas's Small Towns

The United States has an impressive range of regions to explore. Whatever you like mountains, sunshine, snow, or beaches, there's a destination that caters to your desires. A road trip is one of the best ways to experience the diverse beauty of the country, and starting with the Southern route is a fantastic way to begin your adventure.

There are several beautiful states that comprise the South, and Arkansas is one of them. "The Natural State" certainly lives up to its name and is filled with many wonders of nature to explore, from the gorgeous Hot Springs National Park and Blanchard Springs Cavern to the Buffalo National River. Don't just head to the larger cities; check out the charming, smaller towns that are a part of what makes the state so beautiful.

These charming, small towns in Arkansas are worth exploring, and many of them are near or in the Ozark Mountains, so you'll get spectacular views wherever you go. There are also many great shops and restaurants in these towns that you'll want to visit.

Eureka Springs

First on our list of charming small towns in Arkansas you'll want to explore is Eureka Springs. The town gets its name from the fact that it's built around natural springs, so there's a lot of gorgeous greenery and beauty to behold. Walk around town, and you'll also see the wonderful historic district, which is home to old and beautiful buildings, including the Basin Park Hotel, the Palace Bath House, and more.

Of course, there are also many lovely shops and stores to visit. While you walk, don't forget to check out the marvelous architecture of the Throncrown Chapel. You can conclude your visit by heading to the Turpentine Creek Wildlife Refuge. That's where you can get a big thrill by walking through the natural habitat of bears and big cats. Don't worry, it's safe and it's a lot of fun.

Van Buren

Though not as small as some of the other quaint towns on this list, Van Buren is still a great place to visit if you find yourself in the Fort Smith metropolitan area of Arkansas. Take your walking shoes because there's a lot to see here. Stroll through the Van Buren Historic District, and you'll be amazed at how much there is to do.

In addition to magical shops and restaurants, there are also several museums and landmark museums that are stunning architectural marvels. One of those marvels is the Drennen Scott House which was built back in 1836. After you've toured the city, head to some of the greener areas by visiting several of the parks, including the Lee Creek Reservoir Recreation Area, Fort Smith Park, or Louemma Lake.

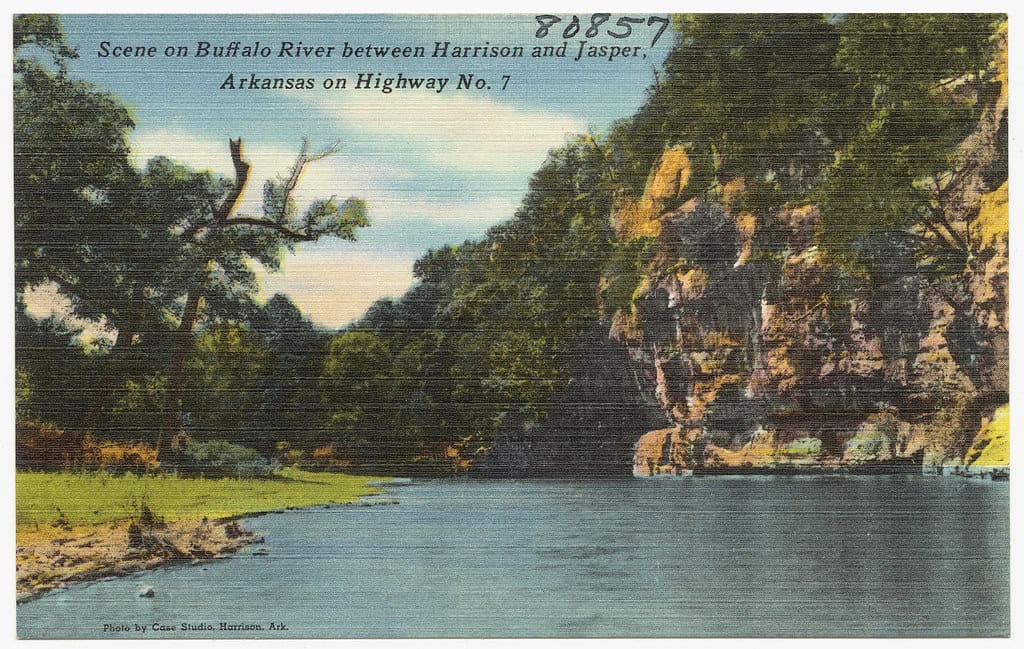

Jasper

Easily one of the charming small towns in Arkansas you'll want to explore is the quaint town of Jasper. This is a small town, but it's surrounded by gorgeous hills and lovely landscapes. This is one of those towns with a Main Street that you can walk down as you stop in local shops and eateries. There are no bars here as this is a dry town, but there's a certain charm to that.

Come here for the atmosphere and for the many fun things to do, from exploring the hiking trails to speaking to the locals. This town is also near many historical landmarks, including the Round Top Mountain Trail, Little Bear Cave Hollow, and the Arkansas Grand Canyon. You could easily spend a weekend here and enjoy every minute of your stay.

Greenwood

Greenwood must have a place on your list of charming small towns in Arkansas you'll want to explore. This is a great town for a quick trip or to stay for a few days. You can tour the quaint shops and restaurants, and you can also travel 30 miles to the larger town of Fort Smith and spend some time there as well.

While you're in Greenwood, stop by Jack Nolen Lake and soak in the natural beauty as you go hiking or enjoy a picnic. You can also stop by Ouachita National Forest and see gorgeous trees and plants, which can be a great learning experience for the kids. In addition to being a nice place to visit, Greenwood is also a great place to raise a family. There are good public schools, it's a safe neighborhood, and the houses are affordable. Pay a visit and see what you think.

Bella Vista

Bella Vista is a gorgeous small town that's situated nicely within the Ozark Mountains. If you love history, there's a lot to see here. Learn more about the past at the Museum of Native American History. Veterans or people who appreciate those in the armed forces can check out the Veterans Wall of Honor. If you love gorgeous architecture, you can stop by the Mildred B. Cooper Memorial Chapel.

It's a huge chapel that combines gorgeous glasswork with stunning arches. Bring your camera because you won't want to miss it. This is a great town to visit if you want to soak in the beauty of the mountains. Hop on the Tanyard Creek Nature Trails to really soak in the beauty. For an extra thrill, take a detour to War Eagle Cavern, which is a living cavern that will really blow you away.

Batesville

History buffs should stop by Batesville because they'll get they'll get their full of Americana. Start by heading downtown, where many of the buildings are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. One of them is the Melba Theater, so stop by for a show. Then, head to the Old Independence Regional Museum and learn about the town of Batesville and what it looked like before.

All that history will likely have you wanting to learn more about the town, so stop by many of the tasty restaurants and cool shops. If you love sports, then head to the Mark Martin NASCAR Museum. It's there where you can see all of the uniforms, memorabilia, and trophies that were owned by the driver. Finally, head down to White River. It's a gorgeous spot that was also a major part of the Civil War. That's just the tip of the iceberg of what you can see here.

Russellville

Another one of the charming small towns in Arkansas you'll want to explore is Russellville. This is a great place to visit if you love nature trails, water activities, and recreational areas. Russellville borders two exceptional bodies of water: the Arkansas River and Lake Dardanelle. Both offer chances to swim and cool off during the hot summer months.

You can also go kayaking, canoeing, and fishing if the mood strikes you. If you like bass fishing, this is one of the best places to be. Next, enjoy a hike through the Ozark St. Francis National Forest or Lake Dardanelle State Park. If you love any type of recreational activity, from skateboarding to baseball, there are plenty of fields and places to enjoy yourself. The town is also very old, so there are many great historical buildings to see along the way.

Mountainburg

There's a ton of charm in the quaint town of Mountainburg. In addition to the various restaurants and lovely shops, there are acres of gorgeous nature to behold. There are many trails that you can hike or bike that go through the mountains. Plan to stop at Artist Point, which is a scenic stop that will put the whole scene in perspective.

If you love camping, then this is a place to add to your bucket list. There's barely any place that isn't beautiful enough to set up camp. There are other charms of Mountainburg, including a dinosaur park. Bring your kids, and they can run around and climb inside many different dinosaurs. The park also offers basketball parks, a running trail, and a large picnic area. Don't forget your camera during your visit to Mountainburg.

Heber Springs

If you're an old-school traveler, you may remember this town by its original name, which was Sugar Loaf. While it's been renamed, it's still a wonderful quaint town that you should visit. The town has been around since the mid-1800s and part of its charm is being home to lovely mineral springs. There's also a large manmade lake that's over 31,000 acres, which makes it perfect for swimming, boating, fishing, and tubing.

Once you're back on land, head downtown to the historic district, where you can see large, beautiful landmarks, such as the town square and the courthouse. You can easily spend a day there while checking out the museum and the numerous thrift and antique stores and then catching a show at the downtown theater. This is a place where you could take the family for a long vacation.

North Little Rock

North Little Rock offers you a refuge away from the hustle and bustle of the larger Little Rock area. Here in this small town, you can be near the big city and even go on a tour there if you want. Then, come back and enjoy the scenery here. There are many scenic trails you can enjoy that go along the Arkansas River.

While you're out, walk through Burns Park, where you'll find gold courses, playgrounds, and even a full-scale amusement park where there's fun for you and your kids. Finally, get your camera and head to the Old Mill. It's a gorgeous piece of architecture from the 1800s that you may recognize from the film "Gone with the Wind." North Little Rock is a nice, safe town where you can unwind and relax. It's so charming that you may never want to leave!

Magnolia

If you're looking for something fun and festive, then one of the charming small towns in Arkansas you'll want to explore is Magnolia. The town is gorgeous and it will remind you of simpler times. Plus, there's a lot of great things to do. You won't know where to start. Check the calendar ahead of time and visit during the annual Magnolia Blossom Festival and soak in the beauty of the season before participating in the World Championship Steak Cookoff.

If you enjoy BBQ, then you might go to Magnolia to see the World's Largest Charcoal Grill. Once your stomach is full, you can go on and learn more about the history of the area by visiting some of the older structures. They include the South Arkansas Heritage Museum and the Columbia County Jail. Finally, take your bike to Logoly State Park and explore the trails.

Altus

You may not have realized that Arkansas has a flourishing wine country. It's a fact, and the quaint town of Altus is at the heart of it all. Travel throughout the town, and you'll come across four separate vineyards. You can tour and enjoy each of them. While you do, you can get a spectacular view of the Ozark mountains.

All the wineries are of the finest quality, so if you're a fan, you need to check them out. There are other fun things to do in Altus, including stopping by the amazing St. Mary's Catholic Church and hiking through the many parks in the area. Of course, you can have a wonderful time just walking down the main streets. There are many friendly people, tasty restaurants, and fun shops to discover along the way.

Siloam Springs

There's something for everyone to do in the quaint town of Siloam Springs. It's near the water, so you can go swimming or visit the City of Siloam Springs Kayak Park. If you enjoy other types of adventure, you can also find trails for hiking and biking throughout the town. This place is a must-see if you love history. The town of Siloam Springs is located within the Cherokee Nation, so there's a lot to discover about the local residents.

To learn more, head by the Siloam Springs Museum Society, where you can get up close and person with many artifacts and exhibits that show you just how amazing this small town has been over the years. You'll likely be amazed at the lovely homes in this town that are likely unlike what you have seen at home. It's quite a lovely experience.

Murfreesboro

Murfreesboro is easily one of the most unique small towns in all of Arkansas. This is a geographical attraction that must be on every travel bucket list because it's where you'll find the Crater of Diamonds State Park. It's a place where you can find real diamonds and shiny bling. This is one of the few places where the public is invited to find their own diamonds, so bring the kids.

After that, stick around and visit Daisy State Park where you can hike and walk through the wilderness, go fishing, or just lay back and relax. There are plenty of great places to stay in Murfreesboro, including the historic Diamonds Old West Hotel. Walk down the city streets, and you'll also see many great restaurants and local shops.

Ozark

If you're looking to see the wonderful Ozark Mountains from a different angle, then add the town of Ozark to your list of charming small towns in Arkansas you'll want to explore. Located on the southern side of the mountain, this town offers many ways for you to relax during your vacation. If you enjoy a sip of wine, you can stop by the Vineyard Vinyasa Retreat and try the newest varieties while soaking in amazing scenery.

Later on, bring your camera to Beatles Park where you can see creative statues and sculptures that are dedicated to the classic band. They'll blow your mind. The park is here because this is the only city that the Beatles ever visited as a band. There's a lot of folk history intertwined in the city of Ozark, so it's worth coming if you love great music.

El Dorado

El Dorado is one of the larger towns on our list, but make no mistake, it's a stunning place that has a small-town vibe. The town is the county seat of Union County, so it has a lot to offer as far as shops, restaurants, and hidden places to discover. There's even an active nightlife scene if you're visiting without the kids. If you do have children, there are still plenty of places to go and discover.

There's the Newton House museum, where you can check out great exhibits that show you how the town has changed over time. Nature lovers have a couple of options here. There's the South Arkansas Arboretum which is packed with colorful flowers that will stir your soul. After that, head to either Oil Heritage Park or Mattocks Park and sit on the grass, have a picnic, or take a walk and soak in the natural beauty.

Fairfield Bay

If you've got a week off of work and you want to visit one of the most gorgeous lakeside resorts in the country, then stop by the small town of Fairfield Bay. As the name suggests, this is the go-to place to visit in Arkansas for all things aquatic fun. There are beaches and water activities galore. You can go boating, skiing, fishing, tubing, or anything else your heart desires.

If you rather have fun on land and you enjoy golfing, then Fairfield Bay is also the place for you. This town has fourteen beautiful golf courses. Try one or all of them and relax on the links. There are a couple of very lovely and quaint lodging options here as well. We recommend staying in the Cobblestone Inn & Suites where you can get an amazing room at a good price, which is great because with so much to do, you won't likely be spending a lot of time there.

Mountain View

Mountain View is a great small town to visit if you love music, especially folk music. This is one of the folk centers of the world. You can get your fill here. Start by visiting the Stone County Museum. That's where you can learn the long history of the folk tradition in Mountain View. Then, walk around town, and you'll see little hints of the folk tradition in stores and restaurants.

If you play an instrument, bring it along, and you could form a band! There are plenty of other fun activities here as well. If you love hiking, you can visit the Ozark Folk Center State Park and then check out the H.S. Mabry Barn. For a little more outdoor adventure, head to Loco Ropes. While there, you can ride fun zip lines and try your hand at unique rope climbing missions.

Mountain Home

The name of this town just screams happiness and relaxation. As the name suggests, this town is situated near the Ozark Mountains, so there are endless opportunities to hike, bike, and enjoy the natural beauty. To get a real thrill, stop by Cooper Park. There's a mountain lake there where you can swim in the freshest of waters.

There are also many different parks in the area, including Keller Park, where you can go hiking or exploring or hit a few balls on the baseball diamond. The town is also home to numerous museums and gorgeous art exhibits that are truly unique. Travel down the streets of the small town and you can see many different shops and stores that you can spend hours exploring.

Rogers

The final entry on this list of charming small towns in Arkansas you'll want to explore is Rogers. Located in Benton County, this city is chock full of history. During your stay, visit the War Eagle Cavern, War Eagle Mill, and Daisy Airgun Museum. They are all beautiful structures that have a lot to teach you about the history of the town.

The museum is particularly interesting because it has a collection of vintage artifacts from years gone by. After a night of exploring, you can check out the numerous restaurants and breweries in town that all have something special to offer. Wake up early the next day and head to Hobbs State Park Conservation Area, where you can walk through nature and breathe in the freshest air you've ever experienced.