Cheese Nips have real cheese and enriched wheat flour. It is made with cheddar cheese, enriched wheat flour, and vegetable oils. Cheez-Its have a crunchier bite and more intense cheesy flavor than Cheese Nips.

- The must-have convenient reference guide for every home cook!

- Includes more than 8,000 substitutions for ingredients, cookware, and techniques.

- Save time and money on by avoiding trips to grab that "missing" ingredient you don't really need.

Cheese Nips Vs. Cheez-Its: What Is The Difference?

©Darryl Brooks/Shutterstock.com

The primary difference between Cheese Nips and Cheez-Its is their flavor. Cheez-Its have a stronger flavor, that's been described as more “authentic” while Cheese Nips have a milder flavor that's sweeter. There are also texture differences with Cheese Nips being soft whereas Cheez-Its are generally described as crunchier.

It should be noted that Cheez-Its are made by Kellogg Company while Cheese Nips are produced by Nabsico. They're similar to Pepsi and Coke in that they're competing brands with slightly different recipes, production, and size of packaging.

Cheese Nips Facts

Cheese Nips were first introduced by Nabisco in 1961. They are square-shaped crackers made with real cheese that have a crunchy texture. Their cheese-packed flavor has made them a long-time favorite amongst snackers everywhere. Cheese Nips come in many variations, including original, reduced-fat, and cheddar flavors.

Cheez-Its Facts

©KK Stock/Shutterstock.com

Cheez-Its were also introduced by Nabisco in 1971. They are round crackers with a delicious cheese flavor and a crunchy texture. Unlike Cheese Nips, the Cheez-Its have holes in the middle that make them easier to chew. They come in several varieties, including original, extra-sharp cheddar, white cheddar, and pizza flavors.

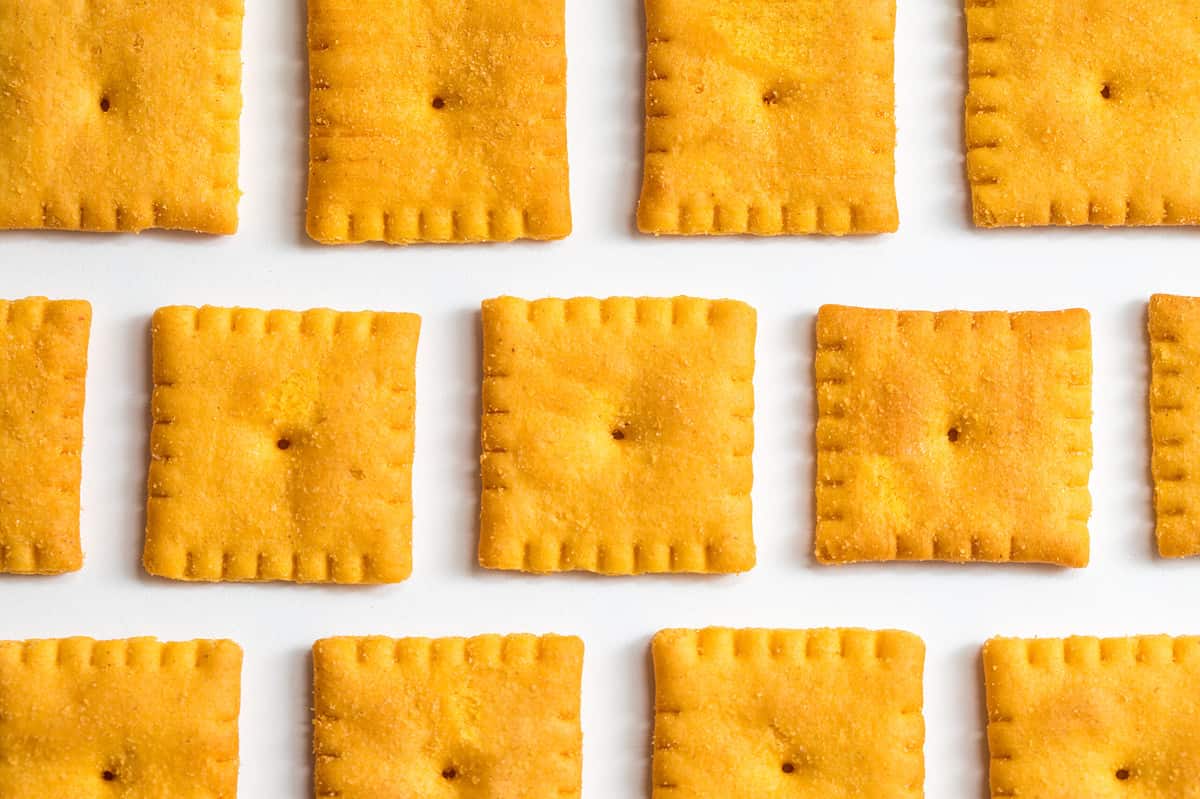

Texture

The most obvious difference between Cheese Nips and Cheez-Its is the shape. Cheese Nips are square-shaped crackers, and Cheez-Its are round, with holes in the middle. The texture of both snacks is crunchy, but they have a slightly different mouthfeel when eaten. Cheese Nips have a denser texture, and the cheese flavor is more pronounced, whereas Cheez-Its are lighter and airier with a milder flavor.

Flavor

Cheese Nips come in three flavors – original, reduced fat, and cheddar. Actual Cheese Nips have a mild cheese flavor that is perfect for snacking and pairing with other foods. Reduced-fat Cheese Nips are made with real cheese but contain half the fat as their original counterparts. The cheddar taste has a stronger cheese taste and is excellent for those who prefer bold flavors.

©Duntrune Studios/Shutterstock.com

Alternatively, Cheez-Its are to be had in 4 exclusive flavors – original, more-sharp cheddar, white cheddar, and pizza. The unique taste is the mildest of all their services and is incredible for snacking on its own or with other foods. The extra-sharp cheddar offers a strong cheese flavor, and the white cheddar has a milder, slightly sweeter taste. Pizza Cheez-Its have an unmistakable pizza taste; this is for those who prefer the classic Italian dish.

Nutrition

There isn't much difference between Cheese Nips and Cheez-Its. It's when it comes to nutrition. Both are made with real cheese and have roughly the same calories for each serving. The reduced-fat Cheese Nips have slightly fewer calories but a higher fat percentage than the original version. The main difference is that Cheez-Its contains more sodium than Cheese Nips and a small amount of added sugar.

What are Cheese Nips?

Cheese Nips are small, crunchy crackers made with a blend of cheddar and Parmesan cheeses. They come in two varieties – Original Cheese Nips and Cheddar Cheese Nips – so there’s something to please everyone’s flavor preferences. Each Cheese Nip is baked to a golden brown and contains no artificial colors or flavors, making them a snack you can enjoy indulging in.

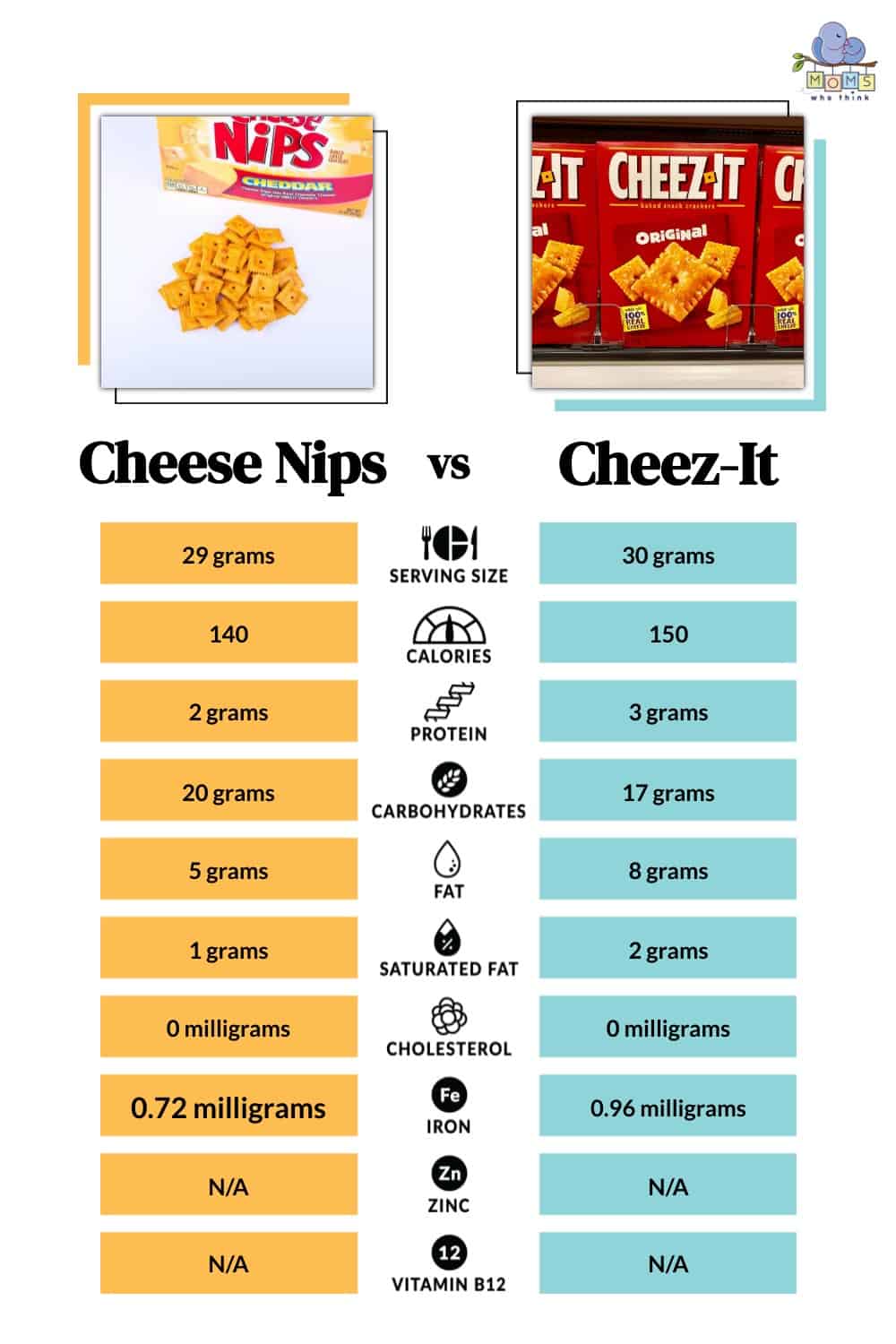

Cheese Nips vs. Cheez-Its Nutrition Comparison: Calories, Fat, Protein

Cheese Nips are a terrific source of calcium and protein. They are also known for their low fat and sugar levels. A 30-gram serving (about 29 crackers) of Cheese Nips consists of approximately 140 calories, 5 grams of fat, 3 grams of protein, and 4% of your daily required calcium intake. This makes them an amazing suggestion for the ones monitoring their calorie intake or looking for something to fill them up without going overboard on sugar or fat.

By comparison Cheez-Its have slightly more calories with 150, the biggest difference between the two is that Cheez-Its have more fat (8 grams) but fewer carbohydrates (17 grams) when compared to Cheese Nips.

- The must-have convenient reference guide for every home cook!

- Includes more than 8,000 substitutions for ingredients, cookware, and techniques.

- Save time and money on by avoiding trips to grab that "missing" ingredient you don't really need.

Storage

Proper storage of Cheese Nips is important as it maintains their flavor and crunchy texture. The best way to store Cheese Nips is by keeping them in an airtight tab or resealable bag. This helps preserve their freshness, flavor, and crunch.

When storing Cheese Nips in an airtight container or resealable bag, keeping them away from moisture, light, and heat is important. Water causes sogginess in the Cheese Nips, making them hard to munch. Light and heat can also affect their texture and taste, making them unappealing.

If you plan to store cheese nips for an extended period, it is crucial to check the expiration date on the package before doing so. While Cheese Nips can remain edible beyond their expiration date, they may not have the same flavor and texture as they did when they were first purchased.

It is also important to store Cheese Nips away from other items with strong odors. Cheese Nips can easily absorb the smell of different foods, which could affect their taste. Keeping them in an airtight container or resealable bag prevents this from happening.

Uses

Cheese Nips have several uses, including snacking, cooking, and baking.

As a snack, Cheese Nips are best enjoyed on their own as a crunchy and savory snack. They can also be served with dips such as salsa or guacamole to add flavor and texture to the snack. Cheese Nips are also a popular choice for school lunches or road trips because they are easy to transport and don’t require a plate or utensils.

Cheese Nips can also be used as an ingredient in various dishes, making them useful for cooking and baking. Cheese Nips are often added to casseroles or macaroni and cheese to add flavor and crunch. They can also be used to make breadcrumbs for coating chicken and fish or as a topping for pizza.

For baking, Cheese Nips can be used to make sweet treats such as cheesecake crusts or pie crusts. Additionally, they can be crushed and turned into a crumb mixture that can be used to top cakes and cupcakes. They are also sometimes used in cookies and other baked goods to add flavor and texture.

All in all, Cheese Nips are a versatile snack that can be used for snacking, cooking, baking, or as part of school lunches. They have a distinctly cheesy flavor that appeals to children and adults alike, making them the perfect snack choice for any occasion.

Varieties

Cheese Nips are small, crunchy, cheese-flavored snacks that come in several varieties, including original, cheddar, and jalapeno. The size and shape of the snack are similar to that of a Goldfish cracker.

The original Cheese Nips were first released in 1965, and the cheddar variety followed in 1975. In 2009, Nabisco added a jalapeno flavor to the line of snacks. This flavor is made with real jalapenos and has become popular among those who enjoy spicy snacks.

Cheese Nips come in several sizes, including single-serve packages, family-sized boxes, and party-sized bags. You can eat them as a snack or make recipes such as cheesy nachos or cheese ball snacks.

In addition to the original cheddar, and jalapeno flavors, Cheese Nips have also been released in other varieties such as bacon and cheddar, sour cream and onion, garlic Paran, and four cheese. These flavors have become among fans of the snack crack who are looking for something different than the original flavor.

What are Cheez-Its?

Cheez-Its is a brand of cheese-flavored, bite-sized snack crackers manufactured by the Kellogg Company. The product was introduced in 1979 and has become a popular staple in American households.

The Cheez-Its recipe includes enriched wheat flour, sunflower oil, cheddar cheese (cultured milk, salt, enzymes, and annatto), salt, monosodium glutamate (MSG), disodium inosinate, and disodium guanylate. The crackers have a distinctive shape with a hole in the center and are dusted with additional cheddar cheese seasoning.

Cheez-Its offer great flavor without being too salty or greasy. They have a crunchy texture and come in several varieties, such as original, reduced fat, extra cheesy, jalapeño jack, parmesan garlic herb, cheddar sour cream & onion others.

Cheez-Its can be enjoyed solo or used as a condiment in recipes like macaroni and cheese, pizza crusts, and casseroles. They make a great snack for kids, party platters, or anytime you need a quick bite.

Cheez-Its are the perfect balance of flavor and crunch.

Storage

Cheez-Its is one of the most popular snacks around, and they're a great option for people looking for a delicious treat without all the unhealthy ingredients. But if you want to ensure your Cheez-Its stay fresh and tasty, it's important to store them properly. Here's how to keep Cheez-Its;

First and foremost, make sure you store Cheez-Its in an airtight container. This prevents them from becoming stale or soggy over time. If the container isn't airtight, transferring your Cheez-Its into a plastic bag or jar with a tight lid is best.

Cheez-Its should also be stored in a cool, dry place away from direct sunlight. A pantry, cupboard, or any other dark and dry spot is ideal. Avoid storing Cheez-Its near any moisture-producing appliances like refrigerators or dishwashers. If your Cheez-Its gets exposed to too much moisture, it may become soggy and less enjoyable to eat.

It's best to store Cheez-Its away from other food items as well. The oils and spices in certain foods may transfer onto your Cheez-Its, changing its taste and texture. Additionally, strong smells like garlic or onions can penetrate Cheez-Its and leave them with an unpleasant odor.

Finally, remember always to check the expiration date on the package of Cheez-Its before you buy them. Even if they're stored properly, Cheez-Its won't last forever – so it's important to enjoy them within their recommended shelf life.

Uses

One popular use for Cheez-Its is as a topping for macaroni and cheese. The crunchy texture of the crackers adds an interesting texture element to what can often be a bland dish. Additionally, adding a small handful or two of Cheez-Its to the top of your dish before baking adds additional flavor.

Another great way to enjoy Cheez-Its is by using them as an ingredient in salads. They provide a nice crunch and savory flavor that pairs well with greens, tomatoes, and other salad ingredients. Cheez-Its are also a great substitution if you prefer a healthier alternative to traditional croutons.

Cheez-Its can also be an amazing way to add crunch and flavor to soups and stews. Sprinkle some Cheez-Its on top of your dish before serving for an added layer of texture and flavor that no one can resist. For a more indulgent soup or stew, try crushing the crackers and using them as a breadcrumb-like topping.

Finally, don’t forget about desserts! Fold in some Cheez-Its if you’re looking for a more convenient way to add flavor and crunch to your cake or brownie batter. The added cheesy flavor will be sure to please even the pickiest of eaters.

Varieties

From mild to sharp, there is something for everyone regarding this popular cheese-flavored snack. Cheez-Its come in various flavors, including cheddar cheese, Swiss cheese, mozzarella cheese, and even jalapeno pepper jack. Each type of Cheez-Its has its unique taste and texture, making them the perfect snack for any occasion.

Cheez-Its have a distinct sharpness that is slightly salty with a hint of sweetness when it comes to cheddar cheese. The Swiss cheese variety has a creamy texture and nutty taste that pairs perfectly with fruits or vegetables. For the air version, some Cheez-Its with mozzarella cheese still have that sharpness but with added richness.

Those who prefer a bit of spice in their snacks will love jalapeno pepper jack Cheez-Its. The combination of spicy peppers and tangy cheese makes for one tasty snack. And if you're looking for something a little different, some Cheez-Its flavors are made with feta cheese and herbs, offering yet another unique experience when it comes to snacking.

No matter which variety of Cheez-Its you choose, they all offer the same delicious flavor and texture. Whether it's on-the-go snacking or lounging around the house, Cheez-Its are a great snack option for everyone.

Can You Substitute Cheese Nips For Cheez-Its?

The answer is yes, you can! Though the flavor and texture may differ slightly, both are still made with real cheddar cheese. Cheese Nips and Cheez-Its are two very popular varieties of cheese snacks. But while they may look similar, they do have some differences.

Cheese Nips are small, round, cheesy bites that make an ideal snack for any time of day. They are baked, unfried, and have a mild flavor that makes them perfect for those who don't like bold flavors. The texture of Cheese Nips is slightly crunchier than cheese, and they come in various flavors such as cheddar, original flavor, stuffed Jalapeno poppers, mozzarella garlic herb, and more.

©Prostock-studio/Shutterstock.com

Cheez-Its is a small, crunchy snack made with original cheddar cheese and baked perfectly. They have a slightly bolder flavor than Cheese Nips and come in three different varieties: Original, Reduced Fat, and White Cheddar. Cheez-Its are usually shaped like a rectangle or square, whereas Cheese Nips are round.

Are Cheese Nips and Cheez-Its The Same Thing?

- Cheese Nips have a milder, sweeter flavor compared to Cheez-Its. Many consumers feel that Cheez-Its taste more cheesy and authentic.

- Cheez-Its have a distinctive crunch that sets them apart from the softer Cheese Nips.

- Both of these delicious snacks are made by separate companies. Cheese Nips are made by Nabisco, while Cheez-Its are made by Kellogg's. The two brands compete with one another with these two products.

Cheese Nips and Cheez-Its are two very similar products. Both are cheesy snacks made with cheddar cheese. But, there are major differences between the two that everyone should know before deciding which one to buy.

Cheese Nips have a light golden-brown color and a slightly thicker texture than Cheez-Its. They are crunchier, with a more intense cheddar flavor. They also contain less fat than Cheez-Its.

On the other hand, Cheez-Its have a slightly lighter yellow color and a thinner texture. They offer a milder cheddar taste and are somewhat greasier than Cheese Nips.

Nutritionally speaking, the two are quite similar. A one-ounce serving of Cheese Nips contains 130 calories, 8 g of fat, and 11 g of carbohydrates. Meanwhile, a one-ounce serving of Cheez-Its contains 140 calories, 7 grams of fat, and 15 grams of carbohydrates.

It comes down to personal preference. If you're looking for a crunchier, more intense cheddar flavor, Cheese Nips may be the right choice. For those who prefer something milder and greasier, Cheez-Its is better suited to your tastes.

Print

Sloppy Joe Mac ‘n' Cheese Recipe

- Yield: 10 servings 1x

Ingredients

- 1 package (16 ounces) elbow macaroni

- 3/4 pound lean ground turkey

- 1/2 cup finely chopped celery

- 1/2 cup shredded carrot

- 1 can (14 1/2 ounces) diced tomatoes, undrained

- 1 can (6 ounces) tomato paste

- 1/2 cup water

- 1 envelope sloppy joe mix

- 1 small onion, finely chopped

- 1 Tablespoon butter

- 1/3 cup all-purpose flour

- 1 teaspoon ground mustard

- 3/4 teaspoon salt

- 1/4 teaspoon pepper

- 4 cups 2% milk

- 1 Tablespoon Worcestershire sauce

- 8 ounces reduced-fat process cheese (Velveeta), cubed

- 2 cups (8 ounces) shredded cheddar cheese, divided

Instructions

- Cook macaroni according to package directions.

- Meanwhile, in a large nonstick skillet, cook the turkey, celery, and carrot over medium heat until meat is no longer pink and vegetables are tender; drain.

- Add the tomatoes, tomato paste, water, and sloppy joe mix. Bring to a boil.

- Reduce heat; cover and simmer for 10 minutes, stirring occasionally.

- Drain macaroni; set aside.

- In a large saucepan, sauté onion in butter until tender.

- Stir in the flour, mustard, salt, and pepper until smooth.

- Gradually add milk and Worcestershire sauce.

- Bring to a boil; cook and stir for 1 to 2 minutes or until thickened. Remove from the heat.

- Stir in the process cheese until melted.

- Add macaroni and 1 cup cheddar cheese; mix well.

- Spread two thirds of the macaroni mixture in a 13 in. x 9 in. baking dish coated with cooking spray.

- Spread turkey mixture to within 2 inches of the edges.

- Spoon remaining macaroni mixture around edges of pan.

- Cover and bake at 375° for 30 to 35 minutes or until bubbly.

- Sprinkle with remaining cheddar cheese; cover and let stand until cheese is melted.

Nutrition

- Serving Size: 1.3 cups

- Calories: 459

- Sodium: 1,140mg

- Fat: 16g

- Saturated Fat: 9g

- Carbohydrates: 54g

- Fiber: 3g

- Protein: 26g

- Cholesterol: 71mg

Best Substitutes For Cheese Nips

Here are some top substitutes for Cheese Nips that are sure to satisfy your craving:

1. Kale Chips – Kale chips have become increasingly popular as a healthy alternative to traditional snacks. Much like Cheese Nips, they are available in different flavors and can be baked or fried for a crunchy snack.

2. Popcorn – Light and airy popcorn is a great replacement for Cheese Nips if you want to reduce calories. It comes in many flavors, including sweet varieties.

3. Hummus and Veggies – For a filling snack, replace Cheese Nips with hummus and crunchy veggies like carrots or celery. It’s high in fiber and protein, which makes it the best choice for those who want to stay full between meals.

4. Pita Chips and Yogurt Dip – Pita chips are a great substitute for Cheese Nips. Try making your own by cutting up pita bread and baking it with olive oil, salt, and spices until crisp. Serve them with a creamy yogurt dip for an extra-special snack.

5. Edamame – For something more savory than sweet, try edamame. It’s a rich source of protein and fiber, making it an excellent choice for those looking to stay energized throughout the day.

Best Substitutes For Cheez-Its

1. Rice Cakes: Rice cakes come in several varieties, including plain, chocolate-covered, garlic-flavored, and others. They have a light, crunchy texture and are often flavored with salt.

2. Corn Chips: Traditional corn chips have a salty taste that can satisfy cravings for Cheez-Its. They may be plain or contain chili-lime seasoning or cheese powder flavorings.

3. Nut Thins: These crackers are made from nuts such as almonds and walnuts. They are crunchy, flavorful, and come in a variety of flavors.

4. Wheat Thins: Traditional wheat thins have the same great flavor as Cheez-Its without all the added fat. Wheat thins also come in many different varieties original, multigrain, mustard-flavored, and more.

5. Tortilla Chips: These chips are typically thicker than the traditional corn chip but have a similar crunch. They come in various flavors, including plain, chili-lime, or nacho cheese.

6. Pita Chips: These baked chips are made from pita bread and provide a unique texture and flavor. Pita chips are available in plain, garlic-flavored, and other varieties.