As a busy parent, it can be challenging to keep up with the latest food trends and make family meals both tasty and simple. With so many varieties of cheese available, it can be difficult to determine which one is best for your next recipe. In this blog post, we will compare two popular cheeses: Colby and cheddar.

While these two cheeses may look similar, they differ in many ways including flavor and texture. Whether you're looking for a tasty addition to a sandwich or a flavorful topping for your next pizza, this post will provide you with the information you need to make the right choice for your next meal. From the tangy taste of cheddar to the creamy goodness of Colby, let's explore all the differences between these two cheeses.

- The must-have convenient reference guide for every home cook!

- Includes more than 8,000 substitutions for ingredients, cookware, and techniques.

- Save time and money on by avoiding trips to grab that "missing" ingredient you don't really need.

Colby Cheese vs. Cheddar Cheese: What Is the Difference?

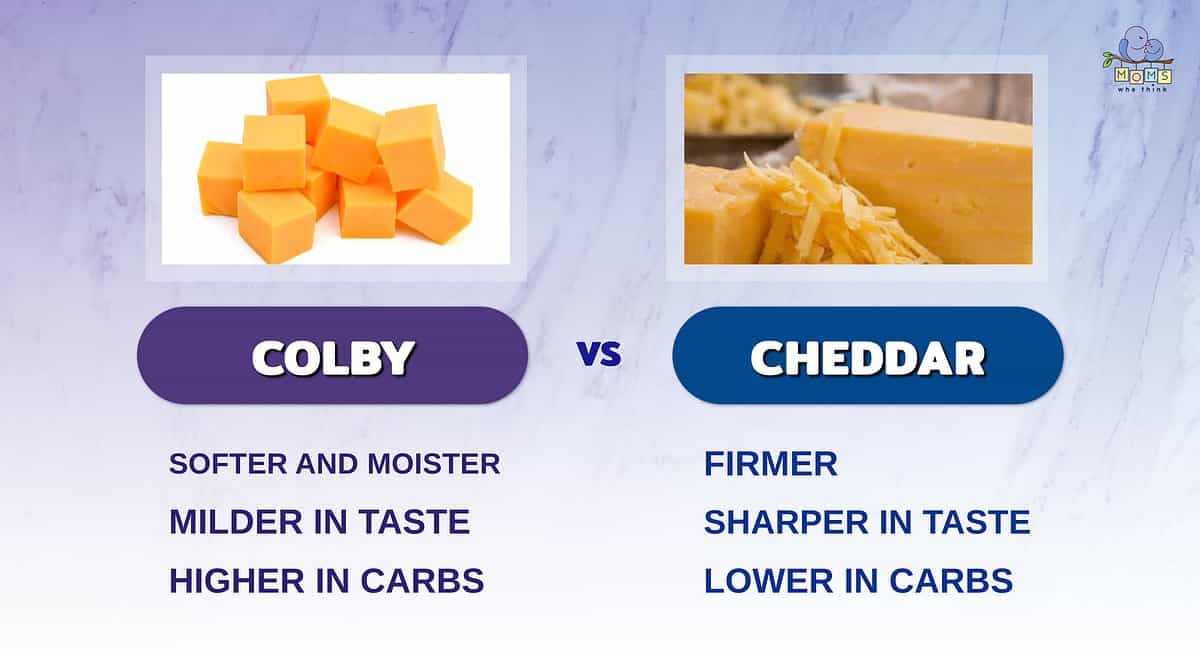

The most important difference between Colby and cheddar cheese is their taste and texture. Colby cheese is softer, milder, and more moist, while cheddar cheese has a more pronounced, sharper flavor that intensifies with aging. Cheddar is also firmer than Colby cheese.

Cheddar cheese is named after the village of Cheddar in England whereas Colby is named after a town in Wisconsin. The difference between the cheeses comes from their production. Cheddar cheese goes through “cheddaring” which further acidifies curds and draws more whey out. It gives Cheddar cheese its dense texture and flavor differences.

Let's take a closer look at each cheese.

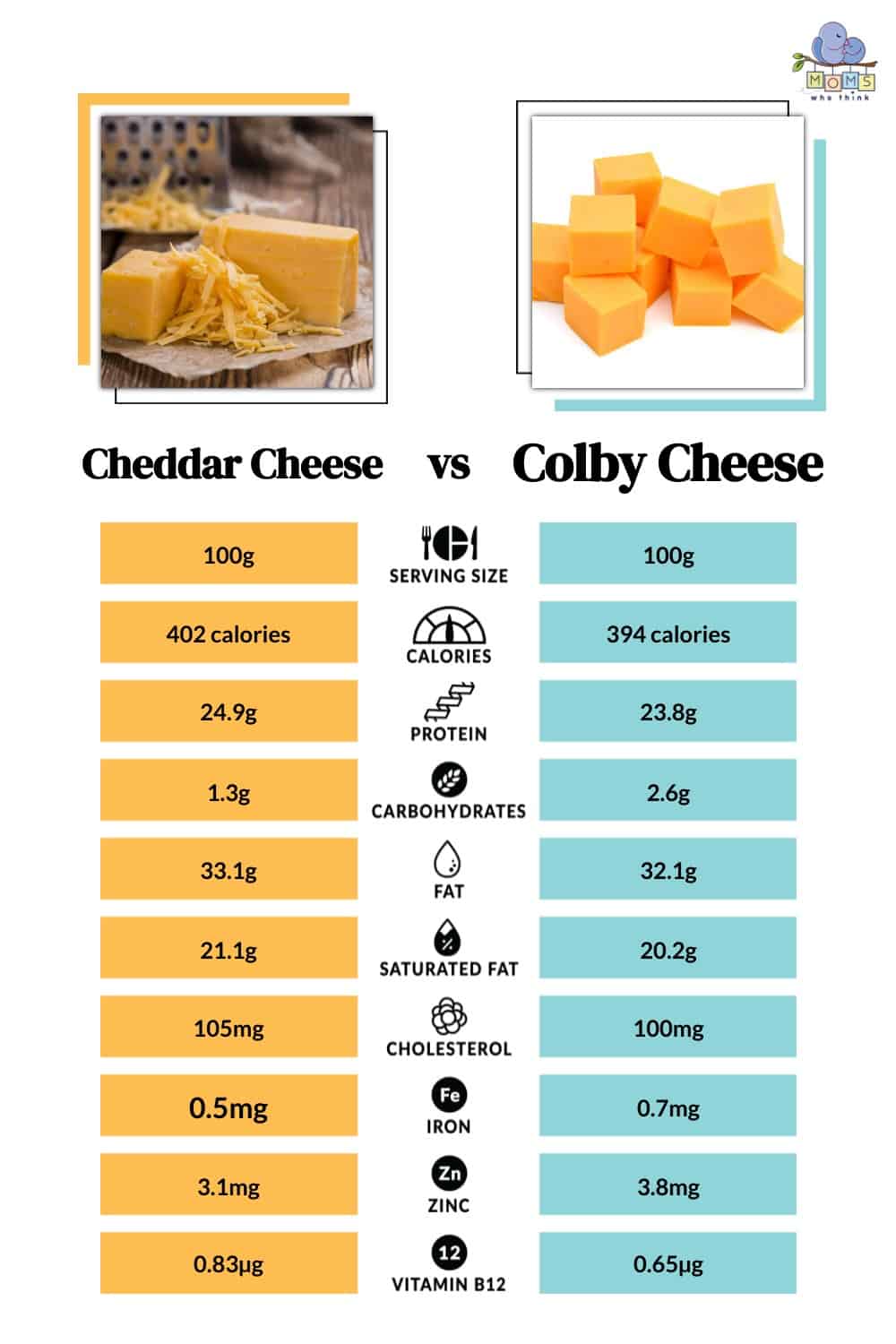

Cheddar Cheese vs. Colby Cheese Nutrition: Which Cheese Has More Calories?

©

Nutritionally, Colby and cheddar cheeses are quite similar. While cheddar may have slightly more calories, both kinds of cheese are high in protein and fat macronutrients while having very few carbohydrates. However, it's worth noting that if you're on a diet that's particularly restrictive for carbohydrates, Colby cheese may have slightly more. As with most cheese, both Colby and cheddar are also excellent sources of calcium.

What Is Colby Cheese?

©Tiger Images/Shutterstock.com

Colby is a semi-hard, cow's milk cheese that originated in America. It tends to be moister, softer, and milder than cheddar, even though both cheeses have an identical coloring that makes them appear similar.

Origin

According to this article from Cheese.com, Colby was first manufactured near Colby, Wisconsin by Joseph Steinwand in 1874. At the time, cheddar was highly popular and primarily produced by cheese manufacturers in the area. Joseph decided to experiment with a different process that involved washing the curds with warm water to remove some of the lactose and create a milder flavor, thus resulting in Colby cheese.

Today, this cheese is still primarily produced in Wisconsin but also in other parts of the country and the world.

Flavor

Colby is a mild cheese, with a buttery and slightly sweet flavor. It also has a mild, tangy aftertaste and is known for being creamier than cheddar.

Texture and Appearance

It has a smooth, open texture with small holes called “eyes” throughout the cheese. This texture is due to the way the cheese is made as it doesn't follow the signature “cheddaring” process of cheddar cheese. Colby also has a higher moisture level than cheddar, making it creamier and excellent for melting.

The coloring of Colby comes from a natural food coloring called annatto. This is the same food coloring that is typically added to cheddar, which is what makes these two cheeses appear the same.

Additionally, there are a few different types of Colby that can be found in the grocery store today. Traditional Colby is what we're covering here and is produced in a rectangular shape. Other types of Colby include:

- Colby-Jack, which is a blend of Colby and Monterey Jack cheese that has a marbled appearance and only ages for 2 weeks.

- Longhorn Colby is a name for Colby cheese that's uniquely molded into a cylindrical shape and can sometimes be simply called “Longhorn cheese.”

How Colby Cheese Is Made

The process of making Colby starts like most other cheeses: Cow's milk is heated, rennet is added to make the milk curdle, and the curds are cut and molded. What sets Colby apart from cheddar and other cheeses is the next step in which the curds are washed with warm water to remove some of the lactose and create a milder flavor. This washing process also helps to create Colby's distinctive open texture with small, irregularly shaped holes throughout the cheese.

Colby is then left to age for one to three months.

Popular Uses

As mentioned, Colby cheese is creamy and excellent for melting so it can often be found in sandwiches, grilled cheese, and as a topping for burgers and other dishes. It's versatility also makes it a popular cheese for snacking, either on its own or with crackers and fruit.

What Is Cheddar Cheese?

©HandmadePictures/Shutterstock.com

While cheddar is also a semi-hard cheese that's made from cow's milk, it originated in England, not the United States like Colby. Cheddar also has a slightly crumbly texture, sharper flavor, and drier consistency than Colby.

Origin

Cheddar cheese originates from the town of Cheddar in Somerset, England dating back as far as the 12th century. As the production process was enhanced over time, techniques were developed for controlling the temperature and acidity of the milk to produce consistent and high-quality cheese. Soon after, cheddar cheese was exported to other countries.

Cheddar cheese is now one of the most popular cheeses across the world. Large cheese factories have been created to meet the growing demand and numerous varieties of this sharp, tangy cheese.

Flavor

As mentioned, cheddar cheese has a distinct, tangy flavor that becomes sharper and more complex as it ages. Fresher forms of cheddar cheese are milder, with a slight buttery flavor while aged versions become more distinct in flavoring.

Texture and Appearance

Cheddar cheese can range in color from pale yellow to off-white, though, like Colby, some manufacturers add annatto coloring to give it its signature golden hue. Unlike Colby which is firm and great for melting, cheddar is a somewhat crumbly cheese.

How Cheddar Cheese Is Made

Cheddar cheese begins its production process the same as Colby: By adding rennet to milk in order to create curdles. The curds are then cut into pieces, pressed, and continually flipped to remove as much liquid (or whey) as possible. What's left is dense, dry, and somewhat crumbly cheddar cheese. This process is unique enough that it's been coined, “cheddaring.”

While Colby has a short aging process, cheddar is aged for much longer. Mild and young varieties of cheddar are aged two to three months. Extra sharp versions are left to age for at least a year and sometimes longer.

Popular Uses

Like Colby, cheddar cheese is extremely versatile. While it can be used on sandwiches, burgers, macaroni and cheese, and soups, it's also popular for snacking and pairs well with fruits, nuts, and crackers.

It's also important to note that the pre-shredded forms of cheddar cheese typically found in your local grocery store include cornstarch to prevent clumping. If you're looking for a stronger flavor and a more creamy melted version, try shredding a block of cheddar yourself.

Can You Substitute Colby for Cheddar?

In general, yes, Colby can be substituted for cheddar and vice versa in most recipes. Keep in mind, however, that these two cheeses have distinct flavors and different textures that may alter your dish.

Cheddar cheese has a stronger, sharper flavor than Colby cheese and a firmer, more crumbly texture. Colby cheese, on the other hand, has a milder, creamier flavor and a smooth, open texture.

While these two cheeses can be substituted in equal amounts for each other, just remember that cheddar will give a bolder, sharper flavor, while Colby will result in an overall milder flavor and creamier texture.

- The must-have convenient reference guide for every home cook!

- Includes more than 8,000 substitutions for ingredients, cookware, and techniques.

- Save time and money on by avoiding trips to grab that "missing" ingredient you don't really need.

Popular Substitutes for Colby and Cheddar

Looking to switch things up in the kitchen or in need of a quick replacement? Here are a few cheeses that work well as substitutes for both Colby and cheddar.

Monterey Jack

As mentioned when we discussed Colby-jack cheese earlier, Monterey jack cheese has a similar texture and mild flavor to Colby cheese. This makes it an easy substitute for recipes like quesadillas or sandwiches.

Muenster

Muenster cheese has a similar texture and mild flavor to Colby cheese. It also melts well, making it a good replacement for dishes like mac and cheese.

Gouda

Gouda has a similar texture to cheddar and depending on its age, can have a mild to sharp flavor. This cheese is a better replacement for the sharpness of aged cheddar as opposed to younger and milder versions of cheddar.

Provolone

This cheese has a mild to sharp flavor and melts well, making it a good substitute for cheddar in dishes like pizzas or on sandwiches. Keep in mind, however, that provolone tends to have a smokier flavor that may affect your dish.

Colby Cheese Recipes

- Replace Colby-jack with regular Colby in this Macaroni and Cheese with Bacon Recipe.

- Simply use Colby in this comforting recipe called Mom's Chicken Noodle Casserole.

- Give this 20 Minute Cheeseburger Rice recipe a milder flavor by using Colby.

Cheddar Cheese Recipes

Print

Cheddar Baked Cauliflower

- Yield: Serves 6

Ingredients

1 large head cauliflower

1 1/3 cups whole milk or half & half

8 ounces aged cheddar cheese (good quality)

3 Tablespoons all purpose flour

4 Tablespoons butter

2 Tablespoons fresh breadcrumbs (optional)

1/2 teaspoon dried mustard

nutmeg

Salt and black pepper

Instructions

1. Preheat oven to 450 degrees F.

2. Trim the cauliflower & break into small florets.

3. Boil in salted water for 10-15 minutes or until just tender.

4. Drain in a colander and then place in a well buttered ovenproof baking dish.

5. Add the milk, flour and butter to a saucepan.

6. Heat to boiling; whisking with a wire whisk continuously until the sauce is thick and smooth.

7. Allow to simmer for 2 more minutes.

8. Add three-quarters of the grated cheese, mustard, a pinch of nutmeg, salt and pepper.

9. Cook for one more minute, stirring well.

10. Pour the sauce over the cauliflower.

11. Mix the remaining cheese and breadcrumbs together, sprinkle over the top.

12. Bake in preheated oven for about 15 to 20 minutes until golden brown and bubbling.

Final Thoughts

- One of the biggest differences between Colby and cheddar is their texture; Colby is soft and moist, while cheddar is quite firm.

- For those who love mild cheeses, Colby is sure to be a favorite. Cheddar is well-known for its sharp and bold flavor, making it a stand-out choice for many sandwiches and other dishes.

- If you're watching your carbohydrates, cheddar is the better choice.

In conclusion, Colby and cheddar cheese are both delicious and versatile ingredients that seem similar but differ in flavor and texture. Colby cheese is mild and smooth while cheddar is sharp and firm. Whichever cheese you choose for your next recipe, it's sure to be a hit!