13 Ice Cream Brands You Should Avoid Due to Recalls

There's nothing more enjoyable in the summer than a refreshing, ice-cold, frosty treat. For many of us, that comes in the form of ice cream or various other frozen goodies. You might not always have your favorite flavors stocked in-house, which is where Mister Softee can save the day. But the popular ice cream truck isn't always around, and you might want to keep a few pints on hand.

However, if you do stock your freezer with delicious desserts, there are certain brands you might want to avoid. According to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), 13 ice cream brands were recalled over potential listeria contamination, a bacterial infection with deadly consequences. Although no illnesses have yet been reported, the FDA recommends you toss all listed items and request a refund from the place of purchase.

Be sure to check the complete recall list here for specific lots and plant codes to verify whether your product was included in the recall. (For more items you should avoid, check out the most unhealthy foods you're likely feeding your kids.)

Friendly's

If you purchased Friendly's brand Celebration Ice Cream Cake (60 fl oz) or Strawberry Krunch Ice Cream Cake (40 fl oz), throw them out.

Jeni's

If you purchased Jeni's brand 3.5 fl oz Chocolate Silk Pie Ice Cream Sandwiches, 3.5 fl oz Key Lime Pie Frozen Dessert, 3.5 fl oz Mint Chocolate Truffle Pie Ice Cream Sandwiches, or 3.5 fl oz Triple Berry Tart Pie Ice Cream Sandwiches, check your packaging.

Hershey's Ice Cream

Perhaps the most recognizable name in the world of sweets, Hershey's brand ice cream is sadly on the list. If you purchased 38 fl oz vanilla and chocolate-flavored ice cream cake, 110 fl oz vanilla and chocolate-flavored ice cream cake, 4 fl oz Cookies & Cream Ice Cream Cones, or 4 fl oz Cookies & Cream Polar Bear Ice Cream Sandwiches, they may need to be tossed.

Abilyn’s Frozen Bakery

If you purchased any of the following products, throw them out: Abilyn’s Frozen Bakery Vanilla & Chocolate 30 fl oz 6” Ice Cream Cake, Abilyn’s Frozen Bakery Vanilla & Chocolate 60 fl oz 8” Ice Cream Cake, Abilyn’s Frozen Bakery “For Love of Chocolate” Ice Cream Cake Abilyn’s Frozen Bakery “Cookies & Cream” Ice Cream Cake Abilyn’s Frozen Bakery “Cookie Dough” Ice Cream Cake.

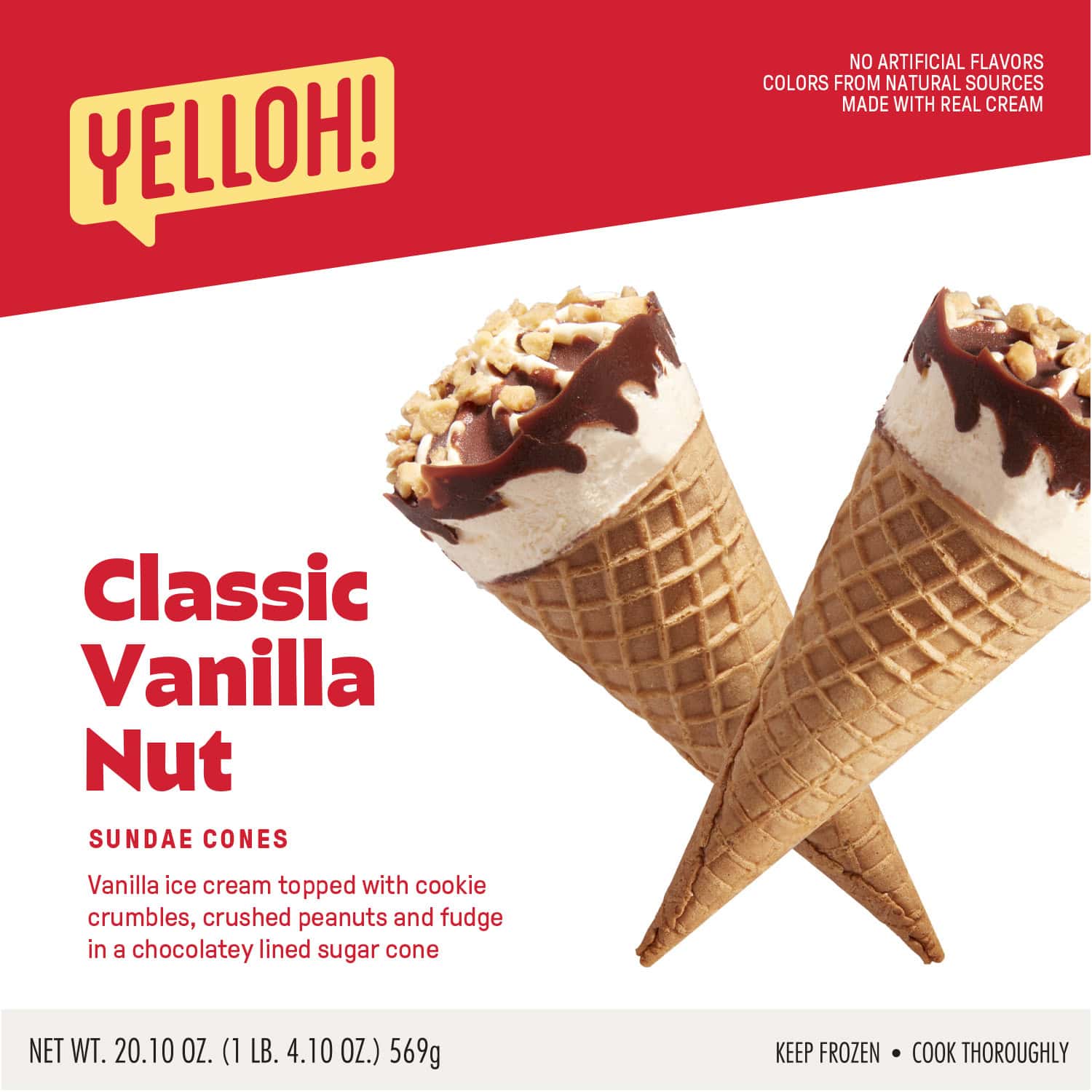

Yelloh!

Yelloh! fans, check your freezer, and if you find any of the following, throw them away: 4 fl oz Vanilla Nut Ice Cream Sundae Cones, 4 fl oz Vanilla Fudge Ice Cream Sundae Cones, 4 fl oz Pecan Praline Ice Cream Sundae Cones, 4 fl oz Chip & Mint Ice Cream Sundae Cones, 4 fl oz Cookies & Cream Ice Cream Sandwiches.

Cumberland Farms

Cumberland Farms' items included in the recall are the Farmhouse Premium Ice Cream Sandwich, Rich Vanilla flavor, 4 fl oz, and the Farmhouse Premium Ice Cream Sandwich, Marvelous Mint flavor, 4 fl oz. Look for codes between 113025 to 120425.

Marco Sweets & Spices

Marco fans, here are the items you need to check and throw out if you have them. Items include 3.8 fl oz Dulce De Leche Ice Cream Sandwiches, 3.8 fl oz Vanilla Chai Ice Cream Sandwiches, 16 fl oz Dulce De Leche & Cookies Ice Cream Pints, 16 fl oz Turkish Mocha Ice Cream Pints, 16 fl oz Vanilla Chai Ice Cream Pints, 16 fl oz Spicy Peanut Butter Caramel and Peanut Butter Caramel Ice Cream Pints, 16 fl oz Moroccan Honey Nut Ice Cream Pints, 16 fl oz Green Tea White Chocolate Ice Cream Pints, and 16 fl oz Aztec Chocolate Ice Cream Pints.

Chipwich

Recalled Chipwich products include the 4 fl oz The Original Vanilla Chocolate Chip Ice Cream Sandwich 10 Club Pack, 3 Pack, and 24 Pack; 16 fl oz Vanilla Chocolate Chip Ice Cream Pint; and 16 fl oz Mint Chocolate Chip Ice Cream Pint.

amafruits

AMAFruits products included in the recall are the 3-gallon Acai Sorbet Tubs and the 3-gallon Dragon Fruit Sorbet Tubs.

Taharka Brothers Ice Cream

Taharka products included in the recall include 16 fl oz Honey Graham Ice Cream Pints and 16 fl oz Key Lime Pie Ice Cream Pints.

Dolcezza Gelato

Dolcezza Gelato unfortunately has a lengthy list of products included in the recall. They include all 16 fl oz pints of Mascarpone & Berries Ice Cream, Roasted Strawberry Ice Cream, Vanilla Bean Ice Cream Pints, Peanut Butter Mash, and Peanut Butter Cup Ice Cream.

There's more though. It also includes all 16 fl oz Dulce de Leche & Cookies Ice Cream, Stracciatella Ice Cream, Peanut Stracciatella Ice Cream, Swiss Chocolate Ice Cream, Coffee & Cookies Ice Cream Pints, Hot Cocoa Ice Cream, Sugar Cookie Dough Ice Cream Pints, Dark Chocolate Ice Cream Pints, and Dark Chocolate Fudge Ice Cream.

LaSalle

LaSalle products included in the recall are 16 fl oz Chocolate Ice Cream Pints, 16 fl oz Vanilla Ice Cream Pints, 16 fl oz Cherry Vanilla Ice Cream Pints, 16 fl oz Vanilla Mango Ice Cream Pints, 16 fl oz Vanilla Raspberry Ice Cream Pints, 16 fl oz Vanilla Fudge Ice Cream Pints, 16 fl oz Dulce De Leche Ice Cream Pints, 16 fl oz Cookies & Cream Ice Cream Pints, and 16 fl oz Butter Pecan Ice Cream Pints.

The Frozen Farmer

There are quite a few treats from The Frozen Farmer that should be tossed if you have them. Recalled items include 4 fl oz Elf On the Shelf Santas Cookies Ice Cream Sandwiches, 16 fl oz Elf On the Shelf Santas Cookies, 16 fl oz Strawberry Sorbet Pints, 16 fl oz Raspberry Sorbet Pints, 16 fl oz Orange Cream Frobert Pints, and 16 fl oz Watermelon Sorbet Pints.