Every mom knows that the almighty noodle is a quick-dinner lifesaver. And thanks to the magic of the internet, the popularity of non-spaghetti noodles is soaring. As a bonus to busy meal-makers, ramen noodles and udon noodles are fast and easy to make, getting dinner on the table in record time.

What Is the Difference Between Ramen and Udon Noodles?

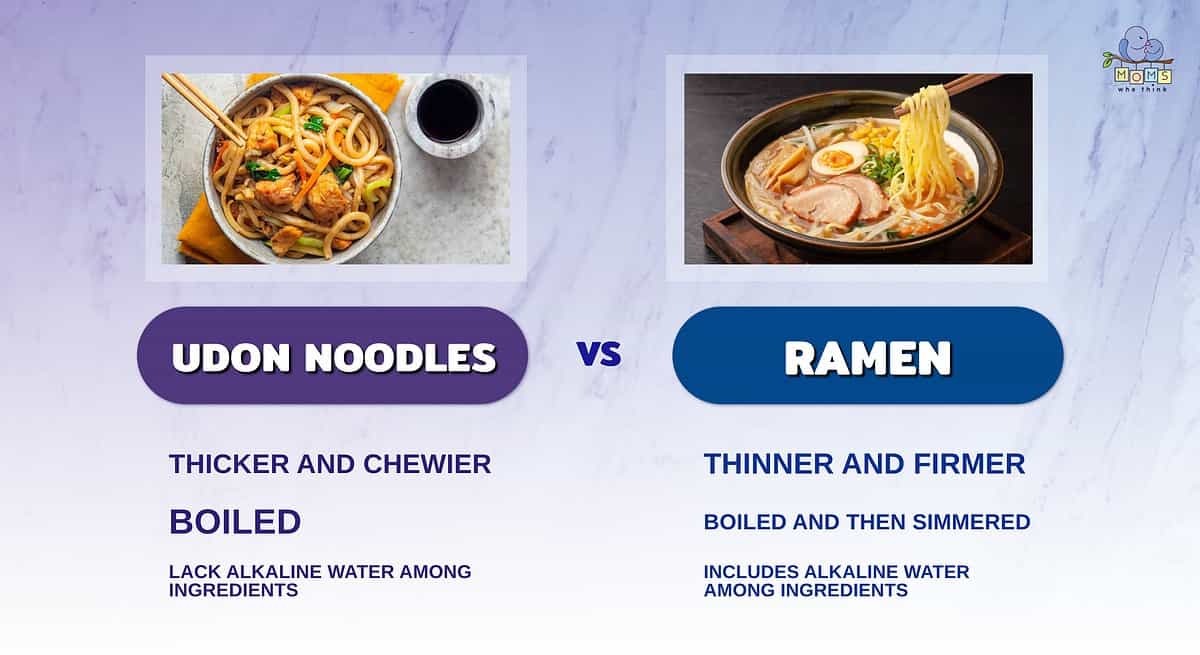

These two noodles are equally delicious and versatile. The differences between them come down to ingredients – and, therefore, texture and flavor – and size. The traditional cooking uses for udon noodles and ramen noodles are different, but those differences come down to culture more than the versatility of the noodles themselves. Ramen noodles are thinner and made with alkaline water which gives them their signature yellow hue, whereas udon noodles are usually thicker and have a gummier texture when cooked.

Noodles are a staple food in many cultures around the world. They come in different shapes, sizes, and textures. You can make them from various ingredients such as wheat, rice, and potatoes. This is due in large part to their proliferation in global cuisines around the world. Two popular types of noodles are ramen and udon. While they may look similar, they differ in texture, flavor, and cooking methods.

Geographical Origins

Ramen and udon noodles both have their origins in Asia, but they come from different regions of the continent. Ramen noodles originated in China and spread to Japan in the late 19th century. Chinese restaurants in the port city of Yokohama initially served them, but they soon became popular throughout Japan. Today, ramen is a popular fast food dish in Japan and around the world, with many regional variations.

©FotoFeast/Shutterstock.com

During the Nara period (710-794 AD), a Buddhist monk who learned the art of noodle-making in China introduced udon noodles to Japan. People believe that the noodles originated in Japan. Udon noodles are especially popular in the western part of Japan, particularly in the Kansai region, which includes the cities of Kyoto, Osaka, and Kobe.

Can I Substitute Udon Noodles for Ramen Noodles?

The short answer is “Yes, but…” Ramen and udon noodles differ in their texture and flavor, but not so much that you can't swap one for the other. Ramen noodles are thin and firm, with a slightly chewy texture. Udon noodles consist of wheat flour, salt, and water, and one typically serves them in a broth made from meat, fish, or vegetables. People often flavor the broth with soy sauce, miso, or salt, and they may add toppings such as sliced pork, egg, and vegetables.

Udon noodles, on the other hand, are thick and soft, with a more doughy texture. Udon noodles consist of wheat flour, salt, and water, and people serve them in a broth made from dashi (a type of fish stock), soy sauce, and mirin (a sweet rice wine). You can add toppings such as sliced beef, fish cakes, and green onions to your noodle bowls.

However, celebrity chefs like David Chang and Roy Choi are deliciously bending and breaking all the rules of both ramen and udon dishes by integrating these noodles into modern crossover recipes, as modern American cuisine heavily focuses on fusion.

If you're going to use these noodle types interchangeably, just make sure you're cooking the noodle you're using according to its specific cooking instructions.

Are Ramen Noodles and Udon Noodles Cooked the Same Way?

Ramen and udon noodles differ in their cooking methods. Boil ramen noodles in water for a few minutes until they are tender but still firm, then drain them and add them to the broth, which should simmer separately. Combine the noodles and broth in a bowl, and add toppings as desired. In traditional preparations, the broth's latent heat continues to cook the ramen noodles en route to the table, making them a perfect toothsome bite when they reach the diner.

On the other hand, boil udon noodles in a pot of water for several minutes until they cook fully. Afterward, drain and rinse them in cold water to remove excess starch and cool them down. Finally, add the noodles to the hot broth and serve.

What Are the Biggest Ingredient Differences Between Ramen Noodles and Udon Noodles?

Traditionally, people make ramen noodles from wheat flour, water, salt, and kansui, an alkaline mineral water, to create thin, wheat-based noodles. Kansui is an essential ingredient that gives ramen noodles their distinct yellow color, firm texture, and chewiness. It also contributes to the springy and elastic nature of the noodles, allowing them to hold up well in a rich and flavorful broth.

On the other hand, udon noodles are thick, wheat-based noodles with a soft and chewy texture. They contain wheat flour, water, and sometimes a small amount of salt. Compared to ramen noodles, udon noodles have a simpler ingredient list and lack the addition of kansui. As a result, udon noodles have a more neutral taste and a softer, doughier texture.

The absence of kansui in udon noodles gives them a white, opaque appearance, setting them apart from the yellowish hue of ramen noodles. Once cooked, the noodles appear semi-transparent. The lack of alkaline minerals in udon noodles also makes them more versatile in terms of pairing with different types of broths, sauces, and toppings. They can absorb flavors more readily and adapt well to various regional and international cuisines.

©Lesterman/Shutterstock.com

What Are Common Mistakes to Avoid When Making Ramen and Udon Noodles?

- Overcooking the noodles: Overcooking the noodles can result in noodles that are too soft and mushy. Don't forget that carryover heat will keep cooking your noodles, so pay attention to the package instructions and pull the noodles out at the early side of the timing window. Remember: you can cook the noodles more, but once you overcook them, you cannot bring them back.

- Undercooking the noodles: On the other hand, undercooking the noodles can result in noodles that are too tough and difficult to chew. Be sure to cook the noodles for the minimum recommended amount of time to ensure the texture is correct, lest your tiny table patrons send the noodles back to the kitchen or demand to speak with the chef.

- Adding oil to the water: Some people add oil to the water when cooking non-pasta noodles to prevent them from sticking together. However, this is not necessary and can actually make the noodles too slippery and difficult to eat. It also prevents the broth (or sauce) from sticking to them.

- Skipping the rinsing step: Rinsing the noodles after cooking is an important step that helps to remove excess starch and prevent everything from sticking together. Skipping this step can result in clumpy and sticky noodles.

- Using cold water to cook the noodles. Both kinds of noodles cook in boiling water, not cold water. Using cold water can result in noodles that are too soft and don't have the right texture.

Best Recipes for Ramen Noodles

We keep these recipes in regular rotation on our dinner tables. (We also love this Serious Eats build-your-own-noodle-bowl article because flavors may vary but results are consistently delicious.)

Best Recipes for Udon Noodles

Udon noodles shine in any bowl where noodles act as a base, but they are especially delicious in these dishes. Curious to learn more about Asian noodle varieties? We broke down Udon Noodles vs. Soba Noodles, another incredible variety.

Print

Asian Noodle Bowl

Ingredients

8 ounce dry udon noodles

2 cups vegetables broth

1/2 cup bottled peanut sauce

2 cups Chinese-style frozen stir-fry vegetables

1/2 cup dry roasted peanuts, chopped

Instructions

1. Cook noodles according to package directions; drain but do not rinse. Set aside.

2. In the same pan, combine broth and peanut sauce. Bring to a boil.

3. Stir in frozen vegetables and cooked noodles, return to boil, reduce heat.

4. Simmer for 2 to 3 minutes or until vegetables are heated through.

5. Divide noodles and broth among 4 bowls.

6. Sprinkle with peanuts.

A Quick Comparison of Udon Noodles vs. Ramen

There's a lot more to ramen than what's sold in packages in the store! This delicious noodle is an important part of Japanese cuisine, and has been for some time. It's thinner and firmer than an udon noodle. Udon noodles have a simpler ingredients list and are only boiled before serving. Ramen noodles are boiled, and then simmered as they are delivered to the table. An interesting ingredient used in the production of ramen is alkaline water- did you know this fun fact about ramen? The next time you serve ramen to your family, you can inform them about this interesting aspect of one of Japan's most famous noodles.

The image featured at the top of this post is ©Coolscene/Shutterstock.com.