As a parent, you love watching your kid have fun. Whether they’re playing outdoors, playing with their toys, or playing with friends, there’s nothing better than seeing a smile on their faces. As you watch them grow and develop, it’s always positive if they can learn while having fun. While it may be difficult to encourage kids at this age to sit down and learn something new, educational toys are an excellent way for them to have fun while they’re learning. To help you choose a new toy for your child, we’ve created a list of the best educational toys for 8-year-olds.

No matter what their interests are, there are numerous toys for your child to play and engage with. These educational toys help them develop necessary skills, practice learning, and foster creativity and independence. Keep reading to find out what they’re currently learning at 8 years old and what toys can help them learn while playing.

©UfaBizPhoto/Shutterstock.com

What Are 8-Year-Olds Learning?

At 8 years old, your child is learning new skills all the time. Although they’re starting to gain more independence, they still love to play with toys, puzzles, and games.

When it comes to educational toys, activities where they can build, learn, and use their imagination are often a great choice. It’s important to keep in mind the developmental milestones they’re reaching at this age as you pick out toys and activities as well.

At 8-years-old, most children will start to:

- Develop more independence

- Connect more with friends

- Learn how to be part of a team

- Become more physically coordinated

- Develop more complex reading skills

- Pay attention to peer pressure and acceptance

There are many changes happening during this time in your child’s life, and it’s essential that they know you’re there to support them. Let’s look at some of the educational toys you can buy to support them as they learn and grow.

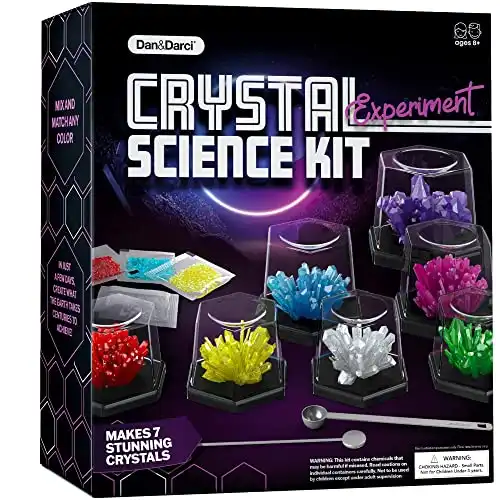

Crystal Growing Kit

Let your child release their creativity with this Crystal Growing Kit from Dan&Darci. This kit allows your child to grow 7 different colorful crystals by mixing the ingredients together and watching them grow. While the instructions and process are simple enough for young children, it will also amaze them and make them feel like real scientists.

The Crystal Growing Kit includes 4 bags of crystal seeds, 7 growing cups and stands, and a measuring spoon. It also comes with a detailed instruction guide that walks your child through the process step by step.

- Crystal growing kit comes with crystal powder, crystal seeds, cups, display stands, and more.

- Immersive educational experience.

- The company provides a 100% satisfaction guarantee or your money back.

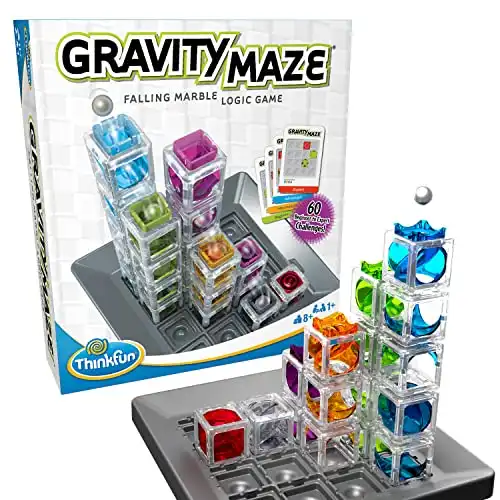

ThinkFun Gravity Maze

The Gravity Maze by ThinkFun is a fun and educational game that’s perfect for 8-year-olds. This maze game will challenge your child and help them learn through 60 different challenges. It’s great for enrichment or for working with STEM learning.

When playing this Gravity Maze game, your child will learn about different STEM, science, and engineering concepts. It includes clear instructions that make it simple for your child to get started on their own.

- Toy of the Year Award Winner

- Engages children in STEM learning

- Includes clear instructions

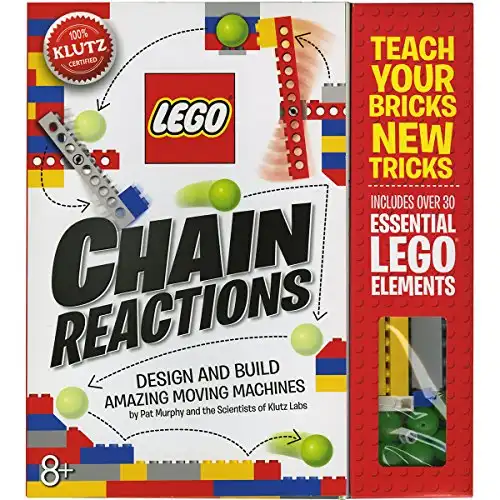

LEGO Chain Reactions

You can’t go wrong when you choose a LEGO gift for your child and if your 8-year-old already loves LEGOs, they’ll love this Chain Reaction LEGO set. This Klutz Certified LEGO kit includes the parts and pieces for your child to turn their LEGOs into machines that move.

While the set includes 33 LEGO pieces, they can also use their own LEGOs to build more sets. It also includes instructions for 10 different modules, 6 plastic balls, string, and paper ramps. Your child will have fun and learn while building these chain reaction machines.

- Explore chain reactions and the engineering world.

- Award-winning LEGO set.

- Clear and easy-to-understand instructions.

- 30 different parts aid in creating ten unique machines.

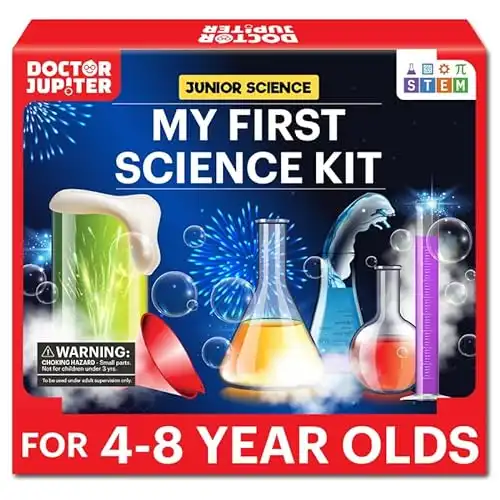

Junior Science Kit

Educational toys that include science are always a hit, especially with kids around the age of 8. This Junior Science Kit is a fun activity for kids at this age and they’ll learn scientific concepts while having fun. It’s simple enough for beginners who haven’t done any science experiments before, but it can be fun for kids of any skill level.

The Junior Science Kit helps your child foster creativity and imagination with over 50 different experiments. The instructions for each experiment are easy to follow and it includes interesting experiments such as Water Fireworks and Walking Water.

- Perfect for beginners

- Great for STEM learning

- Easy to follow along with

National Geographic Microscope Science Lab

Your child can experience what it’s like to have their very own microscope with this Microscope Science Lab Kit by National Geographic. The microscope includes large focus knobs for kids, an adjustable platform, and three levels of magnification.

The kit also comes with 6 plant slides for your child to test out right away. It also comes with 6 blank slides so they can find their own specimens to study. The Microscope Science Lab is a complete kit that comes with everything they need from tweezers to a specimen dish. It also includes simple instructions they can follow independently.

BrainBolt

Let your child train their mind to have better memory with this fun memory game. BrainBolt isn’t as simple as it seems, but it’s a great way for 8-year-olds to practice memorization. This game also helps your child develop problem-solving skills and build confidence in their memory skills.

BrainBolt allows your child to challenge themselves or even their friends by remembering what the light sequence was. They can play solo or in the two-player mode with a sibling or friend.

- Lights up a pattern that children must follow along to for as long as they can.

- Great for any kids over the age of 7.

- Offers a two-player mode so friends can play, too.

Oversize Magnetic Tiles

Magnetic tiles are a huge hit with kids of all ages, but they’re also a great educational toy. While they’re fun to build with because of the different shapes and colors, they’re frequently used for STEM learning as well.

You can use this magnetic tile set to teach about magnetic properties or spatial skills. There are numerous ways to use them or your child can simply use their imagination to build various structures. This brand is compatible with other types of magnetic tiles if your child already has a set.

- Great for STEM learning

- Includes 100 pieces

- Compatible with other magnetic tile brands

STEM Building 7-in-1 Model Kit

Modeling and building kits are the kind of hands-on activity 8-year-olds love. This 7-in-1 Model Kit is fun, engaging, and educational for children. The STEM Building Kit comes with 171 pieces and allows your child to build 7 different model cars.

It’s a great STEM activity and an opportunity to learn and teach about engineering concepts. They can build various models such as a motorcycle, helicopters, and tractors. They’ll have fun while also building confidence and learning problem-solving skills.

- Comes with 171 pieces

- Great for STEM learning

- Teaches critical thinking and problem-solving skills

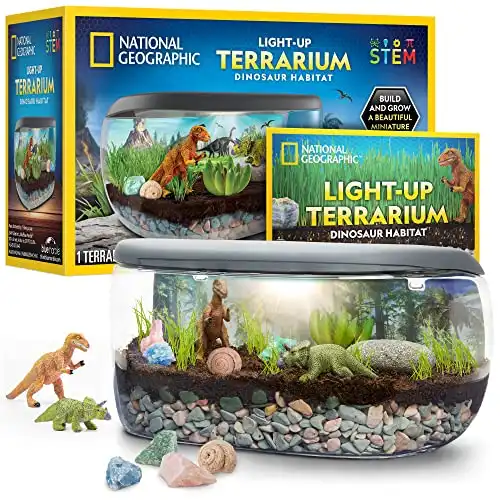

National Geographic Light-Up Terrarium Kit

Terrarium kits are a great way for young children to learn about science and nature. This Light-Up Terrarium Kit from National Geographic is the perfect combination of fun and education. The National Geographic Light-Up Terrarium Kit allows your child to create their own dinosaur terrarium, which is essentially a live, indoor garden.

This terrarium is also unique because it lights up with USB-powered lights. It includes real fossil and rock specimens that make it a great learning experience for your child and something they’ll want to keep in their room forever.

- Lights up with LED lights

- Includes a genuine gastropod fossil

- Perfect for smaller hands

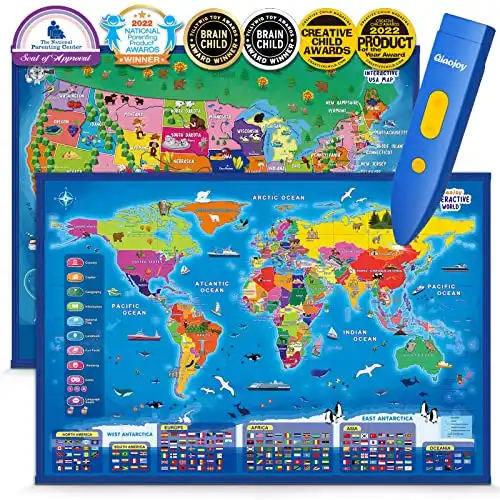

Bilingual Interactive Map

The Bilingual Interactive Map from Qiaojoy is the perfect way for kids to learn about geography and study the world around them. This map comes in a variety of options and has won multiple awards. It also received the seal of approval from the National Parenting Center.

This map is an interactive talking map that speaks in both English and Spanish. It includes 10 interactive features and over 2,000 geography facts about the United States for your child to learn. It also includes over 3,000 facts about the various countries across the world.

- Award-winning interactive map

- Teaches in both English and Spanish

- Includes thousands of fun facts

Finding the Best Educational Toys for 8-Year-Olds

Educational toys are a great way to encourage your child to learn and have fun while doing it. No matter what their skill level is, these educational toys are great for 8-year-olds with all kinds of different skills and interests.

This list of the best educational toys for 8-year-olds has something for young boys and girls, no matter what their interests are. Whether it’s time for some new toys to play with or they have a birthday coming up, consider one of the educational gifts on this list.

The image featured at the top of this post is ©SOMRERK WITTHAYANANT/Shutterstock.com.