If you have fussy, young eaters in your home, a tater tot casserole can be the perfect thing to serve on any given night. Here's a bit of background on this beloved hotdish as well as a handful of recipes to help you serve it up hot.

What are Tater Tots?

Tater tots can be described as potatoes that are grated and fried. Cylindrical in shape, they are often served as a side dish, but in the below recipes, they take center stage.

Variations of this casserole — also referred to as tater tot hotdish — can be found all over the world. The name tater tot is trademarked by the Ore-Ida company, but it's often used as a generic term for this type of fried potato recipe.

History of Tater Tots

Tater tots originated in 1953 when the founders of the Ore-Ida company were trying to figure out what to do with leftover slivers of cut-up potatoes. They decided to chop them up and add flour and seasoning. The product was then shaped and fried, and the tater tot was born.

When tater tots were first introduced in stores, they were so inexpensive that people were hesitant to buy them thinking they were low in quality. When Ore-Ida raised the price, they began to sell more of the product and, eventually, they went on to become the popular food item they are today.

Tater tots are easily found in major grocery store chains. They can also be found on school lunch menus and as side dish options at countless restaurants.

Tater Tot Casserole Recipes: The Options are Endless

As with any casserole dish, a tater tot casserole can be made in a variety of ways. For the most part, they are soup-based and will include ground beef and various vegetables. One of the below recipes uses both cream of mushroom and cream of chicken soup as well as ground beef and green beans. The other showcases just four simple ingredients: beef, cream of mushroom soup, Cheez Whiz and tater tots.

How to Make Tater Tot Casserole

The first recipe requires preparing the meat and mixing it with the soup, vegetables, and seasonings. Then pour the mixture into a casserole dish and layer it with the tater tots for a meal your family will love.

But when we think of tater tot casserole recipes, the sky is the limit. Here are some variations on the classic that you might enjoy making:

Sloppy Joe Tater Tot Casserole

Although you can prepare this recipe using sloppy joe from a can, home cooks will prefer to make theirs from scratch using ground beef, sauce, vegetables, and seasonings. Once the sloppy joe mixture is prepared, put it in a casserole dish as the base layer, add cooked tater tots and serve.

Slow Cooker Tater Tot Casserole

A slow cooker can be perfect for preparing your meat mixture as it will allow all the flavorings to come together. Add the meat, veggies, and sauces of your choice and simmer in your slow cooker. When it’s done, just add the tater tots and you’ve got yourself a great meal.

Cheesy Tater Tot Casserole

Cheese is an ingredient that can take your tater tot casserole to the next level. To make a cheesy tater tot casserole, just prepare the combination you prefer, sprinkle cheese over the top and bake.

Tater Tot Casserole with Beef

Most tater tot casserole recipes include ground beef. This is a great addition as it goes well with tater tots and serves to make the meal hearty. It is also rich in protein and iron. It may protect your heart and lift your mood.

However, not every tater tot recipe calls for beef. Some recipes use other types of meat and some don’t use meat at all. Here are some examples of tater tot recipes that feature these variations.

Cauliflower Tater Tot Casserole

A veggie lover’s dream, this dish features cauliflower, bread crumbs, cottage cheese, cheddar cheese, chicken and a variety of seasonings. The cauliflower is made into a rice-like texture and chicken, cheese and tater tots are added to layered perfection.

Chicken Fajita Tater Tot Casserole

This recipe requires a tater tot base which includes egg, cream, milk peppers, cheese, onions, sour cream, and various seasonings. The chicken is then layered over the top.

Bacon Cheeseburger Tater Tot Casserole

What isn’t better with bacon? This take on the recipe involves mixing the beef, tater tots, cheese, bacon bits, cheese soup, and sour cream. Once the ingredients are mixed, simply put them in a casserole dish and serve.

Recipe Cards: Add These Options to Your Recipe Box!

A tater tot hotdish is a delicious and hearty meal that is great for kids, and parents will love it too! This first recipe we have here is pretty basic, but with so many variations available, you can play with the ingredients to create a dish that will please a wide range of taste buds and meet any dietary need.

Print

Tater Tot Casserole

- Total Time: 45 Minutes

Description

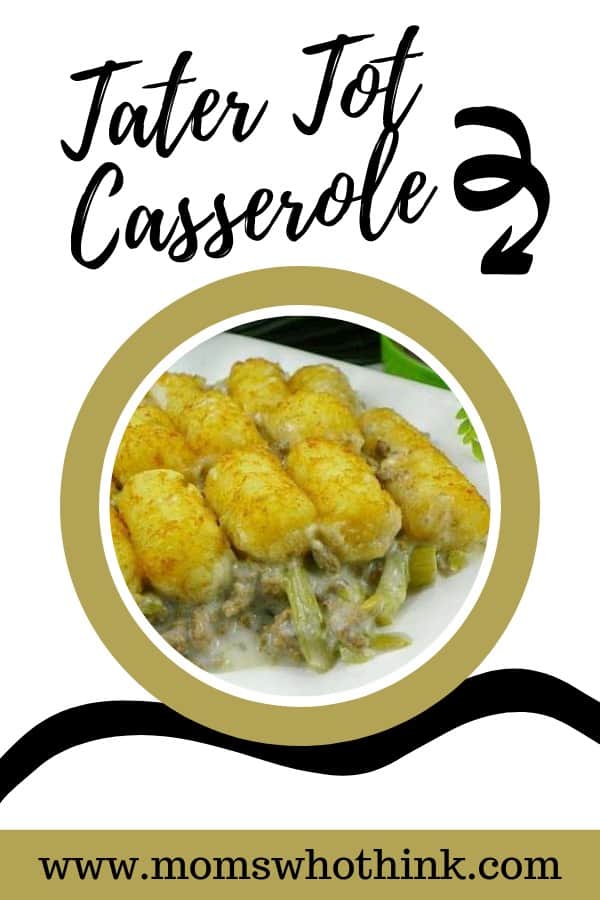

This kid-friendly ground beef casserole goes from kitchen to table in 35 minutes. Crispy bites of potato form a crust on this ground beef, green bean and creamy gravy dinner classic.

Ingredients

- 1 pound ground beef

- 1 (10.75 ounce) can condensed cream of mushroom soup

- 1 (10.75 ounce) can condensed cream of chicken soup

- 1 cup whole milk

- 1 teaspoon garlic powder

- 1 teaspoon salt

- 1/2 teaspoon pepper

- 1 (14.5 ounce) can French style green beans

- 1 (32 ounce) package tater tots

Instructions

- Preheat oven to 375 degrees F (190 degrees C).

- In a large skillet over high heat, brown the ground beef and drain fat.

- Stir in condensed cream of mushroom soup, condensed cream of chicken soup, milk, garlic powder, salt, pepper and green beans.

- Pour the mixture into a medium-sized casserole dish and layer with the tater tots.

- Bake in preheated oven for about 30 minutes, or until tater tots are browned and crispy.

- Prep Time: 15 Minutes

- Cook Time: 30 Minutes

- Category: Main Course

- Method: Baking

- Cuisine: American

This next recipe comes from a trusty source: my Minnesota mother-in-law! She calls it tater tot hotdish. Call it what you like. It will become your family favorite regardless. In fact, he makes this recipe pretty frequently as it conjures fond memories from his childhood.

Print

Tater Tot Casserole (My Minnesota MIL's Recipe!)

Description

This family recipe comes from my mother-in-law's recipe box. It's a touch of nostalgia and a whole lot of comfort all in one well-greased casserole dish.

Ingredients

- 2 lbs ground beef

- 1 can cream of mushroom soup

- 16 oz jar of Cheez Whiz

- 1 32–oz bag of Tater Tots

- Salt & pepper to taste

Instructions

- Preheat the oven to 350 degrees F.

- Brown the ground beef, and drain.

- Spray your casserole dish with Pam or similar product.

- Pour drained, cooked ground beef into the bottom of the pan.

- Cover the beef with cream of mushroom soup.

- Slather on Cheez Whiz.

- Add an even layer of Tater Tots.

- Bake at 350 degrees F for 1 hour, 15 minutes.

- Season to taste and enjoy!

How will you be preparing your tater tot casserole tonight?

The image featured at the top of this post is ©iStock.com/bhofack2.

(4 votes, average: 4.25 out of 5)

(4 votes, average: 4.25 out of 5)