Test Your Knowledge of WWII With These Questions Most Americans Get Wrong

To date, World War II is the deadliest conflict in human history, marked with the highest death toll, both civilians and soldiers, and the genocide of six million Jews. The war was fought on a truly global scale, involving around 70 nations, and took place on three continents–Europe, Africa, and Asia–as well as the three major oceans. Without the past and what occurred, the world we live in might not be the same. It's important to learn history to avoid repeating these mistakes of the past.

At Moms Who Think, we believe one of the most important aspects of a person's life is education, and it is disappointing and rather alarming to see how poorly most Americans perform on standard history tests. With so many details, remembering everything might not always be the easiest but we've put together a list that will allow you to test your knowledge of WWII with these questions that most Americans get wrong.

Question

The Axis Powers consisted of which three countries?

Answer: Italy, Germany, and Japan

While other countries were at times associated with the name the Axis Powers, Germany, Italy, and Japan were the most influential. Smaller countries included Romania, Slovakia, and Hungary. Adolf Hitler was the leader of Germany, Emperor Hirohito was the leader of Japan and Benito Mussolini was the leader of Italy.

The Axis Powers formed as a way to expand territory at the expense of bordering countries. They claimed to want to defend civilization from communism, but their agreement (formed mostly between Berlin and Rome in 1936) played a large part in sowing the seeds of war leading up to World War II.

In contrast, the Allied forces were essentially the "enemy" of the Axis Powers. The Allied forces consisted mostly of China, the United States, the Soviet Union, and Great Britain. Poland and France were also early members of the alliance, and the Soviet Union stepped in only after being invaded by the Germans.

Question

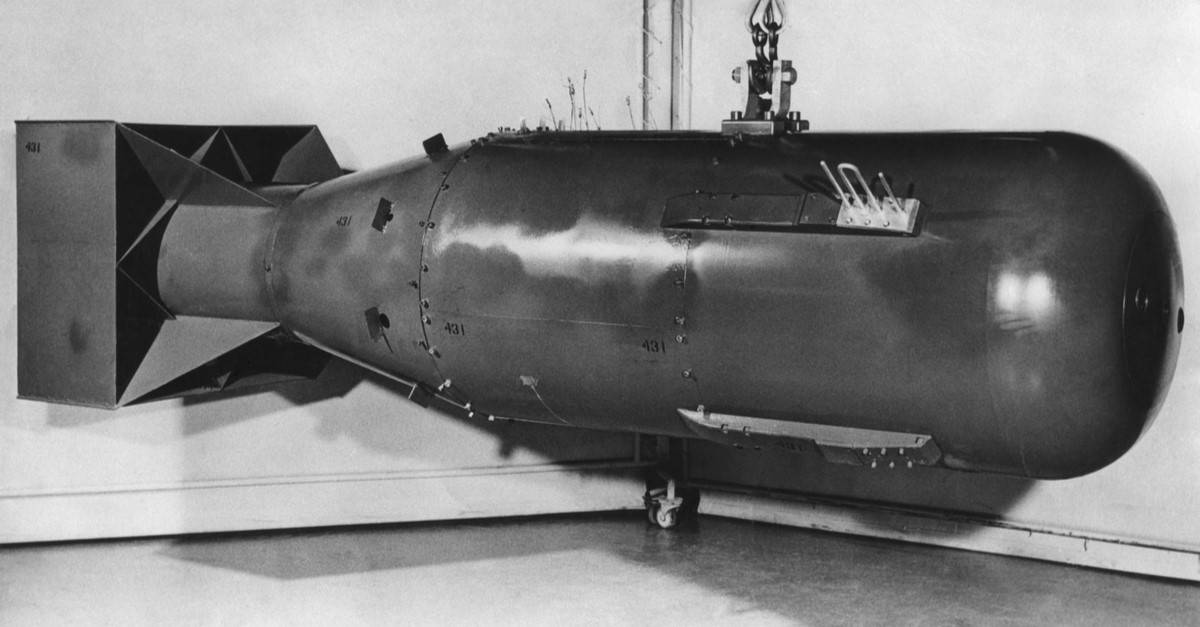

When the nuclear bomb was developed, what was the name of the project?

Answer: The Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a super secret government program formed to create the atomic bomb. The results of the project had a profound impact on the end of the war and warfare since then.

The developers of the nuclear bomb lived in secret military bases in unknown locations with their families to protect them. The fruits of their labors include the two bombs dropped on Japan near the end of World War II, one in Hiroshima and one in Nagasaki. The two bombs dropped killed more than 100,000 people, not to mention the long-term effects of nuclear warfare.

Many claim the United States developed the nuclear bomb before another country had a chance to, and there are now international laws surrounding the use of nuclear warfare.

Question

What was the Blitzkrieg?

Answer: A Nazi Germany Military Tactic

Nazis used the blitzkrieg to quickly defeat enemies. they used infantry, tanks, air support, and artillery to create disorganization and psychological shock against their enemies. The strategy was to place offensive weapons at the front of the attack to keep soldiers occupied, then break deep into enemy territory while outnumbering them.

The German word blitzkrieg translates to "Lightning War" and this tactic helped Germany early in the war. It helped with the 1940 invasion of France and the 1939 destruction of the Polish Army. Elements of it exist in modern conflicts, but the foundation of the tactic traces back to the 19th century.

Question

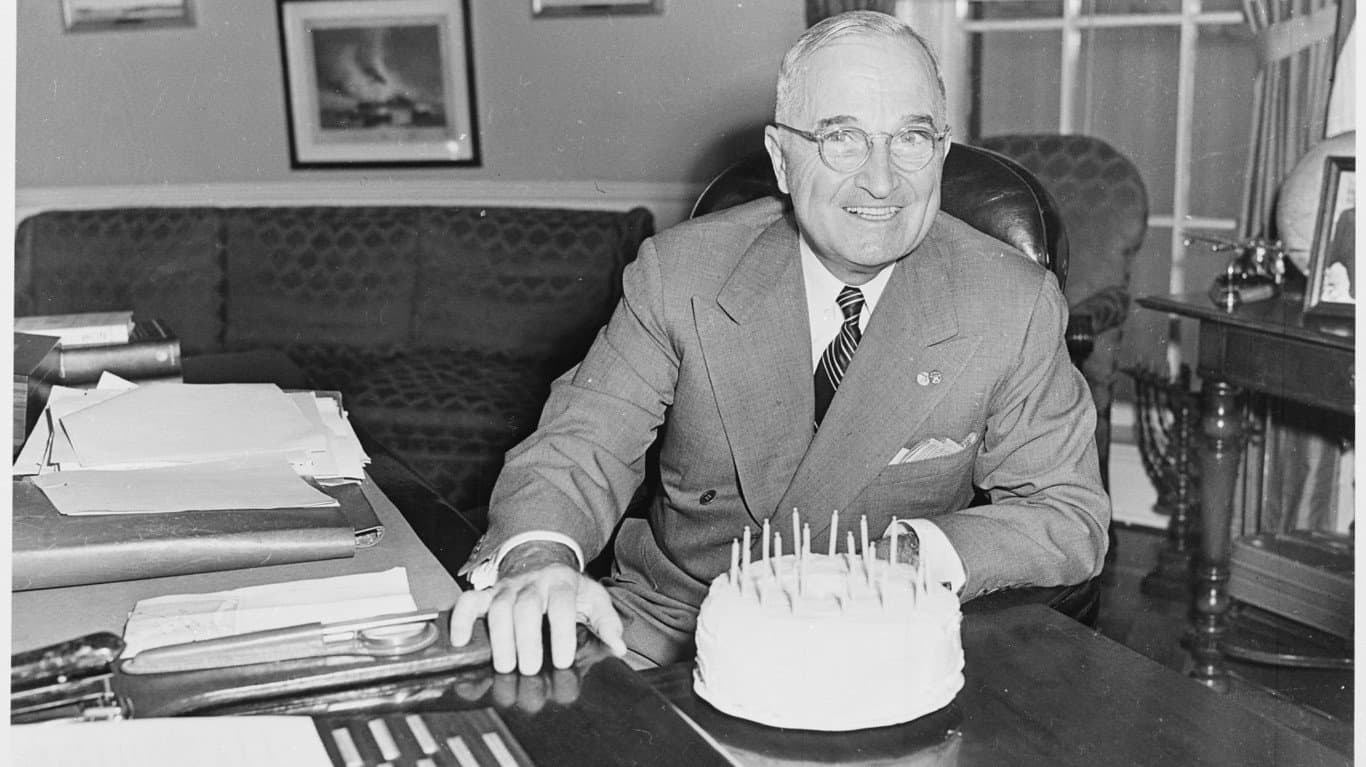

When did World War II officially end?

Answer: 1945

This can be a tricky question because the war ended as different troops surrendered and leaders agreed to peace. From 1939 to 1945, the deadliest war in history raged in Europe, Asia, and the United States.

On September 2, 1945, United States President Harry Truman announced that Japan had officially surrendered. This was the same day Japan signed formal surrender documents aboard a United States Navy ship. The German Third Reich surrendered early on May 7, 1945, in northeastern France.

While the Germans surrendered long before Japan did, the United States engaged in an ongoing battle with Japan as its leaders continued to commit atrocities. The US government decided to drop the atomic bomb as a show of force to Japan, and after two bombings, they surrendered.

Question

What organization was formed after World War II to promote peace?

Answer: The United Nations

Formed in part to avoid another World War as countries rebuilt after a deadly, lengthy one, the United Nations (UN) has several specific goals. They promote human rights, maintain international peace and security, and keep things friendly between different nations.

51 countries founded the UN. The main bodies include the UN Secretariat, the International Court of Justice, the Trusteeship Council, the Economic and Social Council, the Security Council, and the General Assembly. Participating governments fund the UN.

Question

What is the name of the first battle where the German Nazis were defeated?

Answer: The Battle of Stalingrad

The German army and its allies moved from conquering European territory to the Soviet Union. They started with the city of Stalingrad in Southern Russia, and as they and their allies attacked, they were finally stopped by the Red Army, marking their first major defeat in World War II.

In November of 1942, Soviet forces encircled the Germans that were positioned in Stalingrad. The battle lasted until February 1943. The original German force consisted of 220,000 soldiers, while the soldiers who surrendered after the battle consisted of 91,000 forces, leaving Germany weak.

Question

How did the Allies trick the Germans before D-Day?

Answer: False Information and Campaigns

It's hard to imagine a world where information isn't ready at your fingertips at all times, but remember that it took weeks and even months to get reports from one continent to another. Many countries had no idea what was happening in concentration camps until soldiers uncovered the atrocities because there was no way to document and send it quickly. So using false information and campaigns was easier then.

Allied forces sent many dummy tanks and vehicles all over southeast England so Germany was closely watching the area expecting the forces to move there. Fake radio traffic also confused the Germans. This gave the Allied forces a bit of an advantage because while Germany knew there would eventually be a cross-channel invasion, they weren't sure where it would happen.

Question

What's the name of the trials where Nazies were tried after the end of the war?

Answer: The Nuremberg Trials

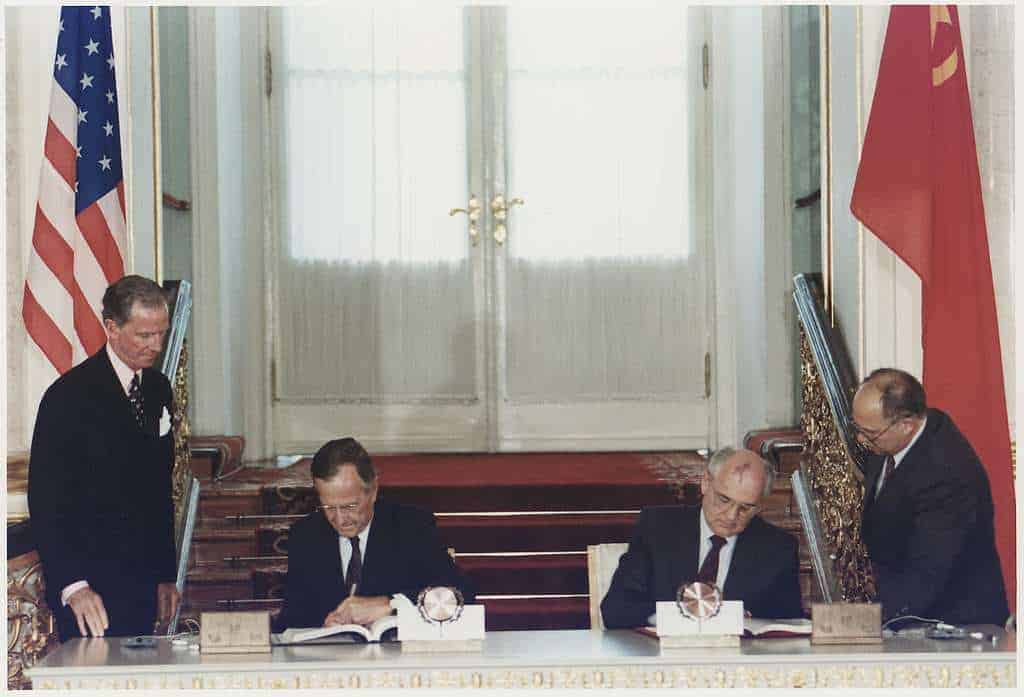

After World War II ended, Allied powers like the Soviet Union, France, Great Britain, and the United States joined forces to form an International Military Tribunal. Nazi German leaders stood trial from 1945-1946 for crimes against humanity, war crimes, crimes against peace, and conspiracy to commit these crimes.

While Germany had a huge army committing many of the war crimes associated with World War II, only 199 defendants stood trial in the Nuremberg Trials. 161 of those defendants were convicted and 37 received a death sentence. Leaders like Joseph Goebbels, Adolf Hitler, and Heinrich Himmler were unable to stand trial because they had already died by suicide.

Question

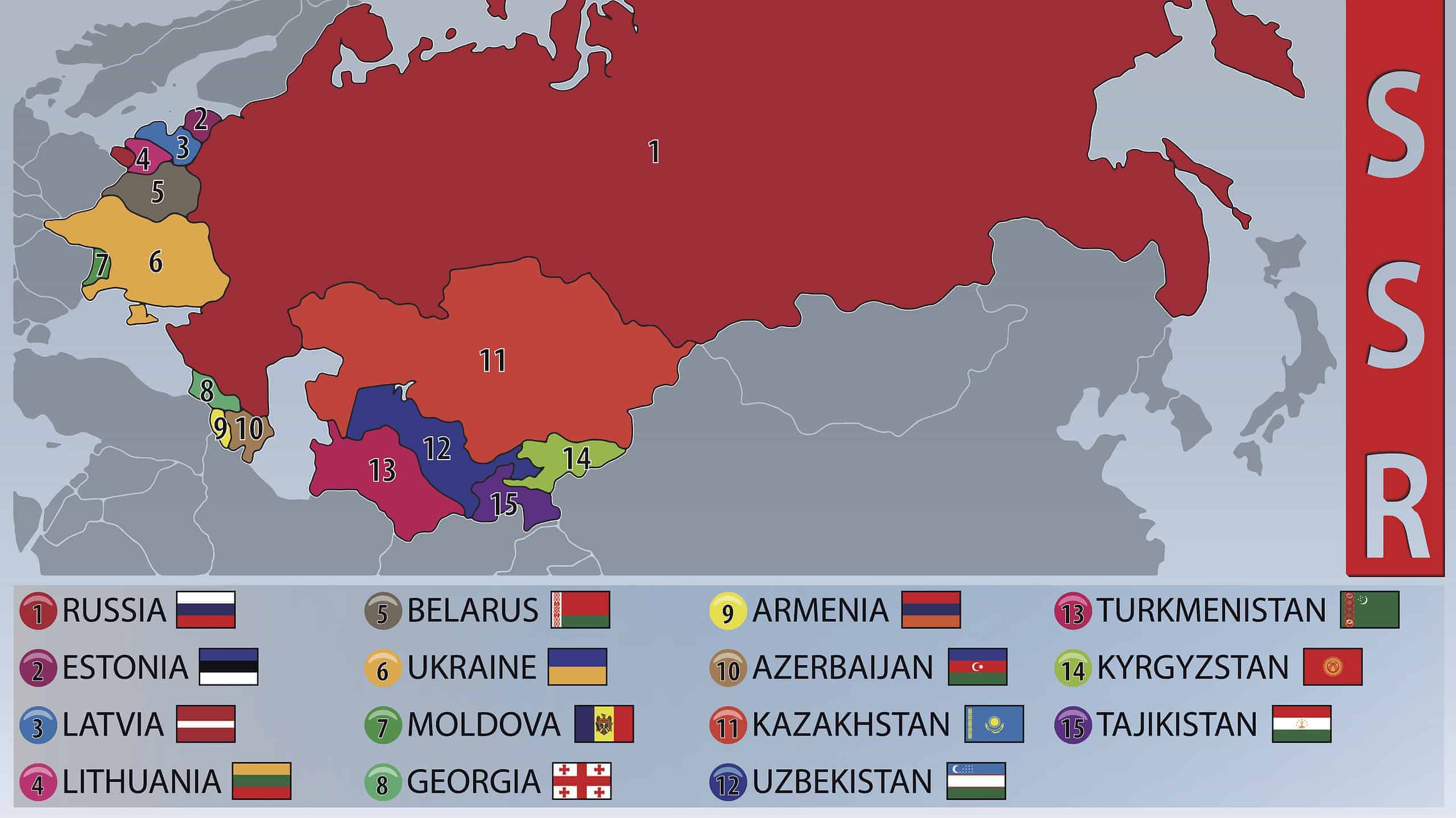

Which countries lost the most civilians during World War II?

Answer: The Soviet Union

Formerly known as the Soviet Union, this area split into different countries. During World War II, they lost around 19 million civilians. On top of that, they also lost 8.7 military members. To put that into context, German forces only had 5.3 million military casualties.

The Republic of China came in second but disputed how many civilians and military members they lost. Between the two areas, they account for more than half of the total civilian deaths from the war.

Question

What do we now call the Allied invasion of Normandy?

Answer: Operation Overlord or D-Day

Commonly referred to as D-Day, the military operation was the beginning of the end of the war and took unbelievable amounts of communication between the Allied powers. On June 6, 1944, sea, air, and land forces of the Allied armies completed the largest amphibious invasion in military history. The operation had the codename OVERLORD and included 7,000 ships manned by 195,000 personnel from eight different countries.

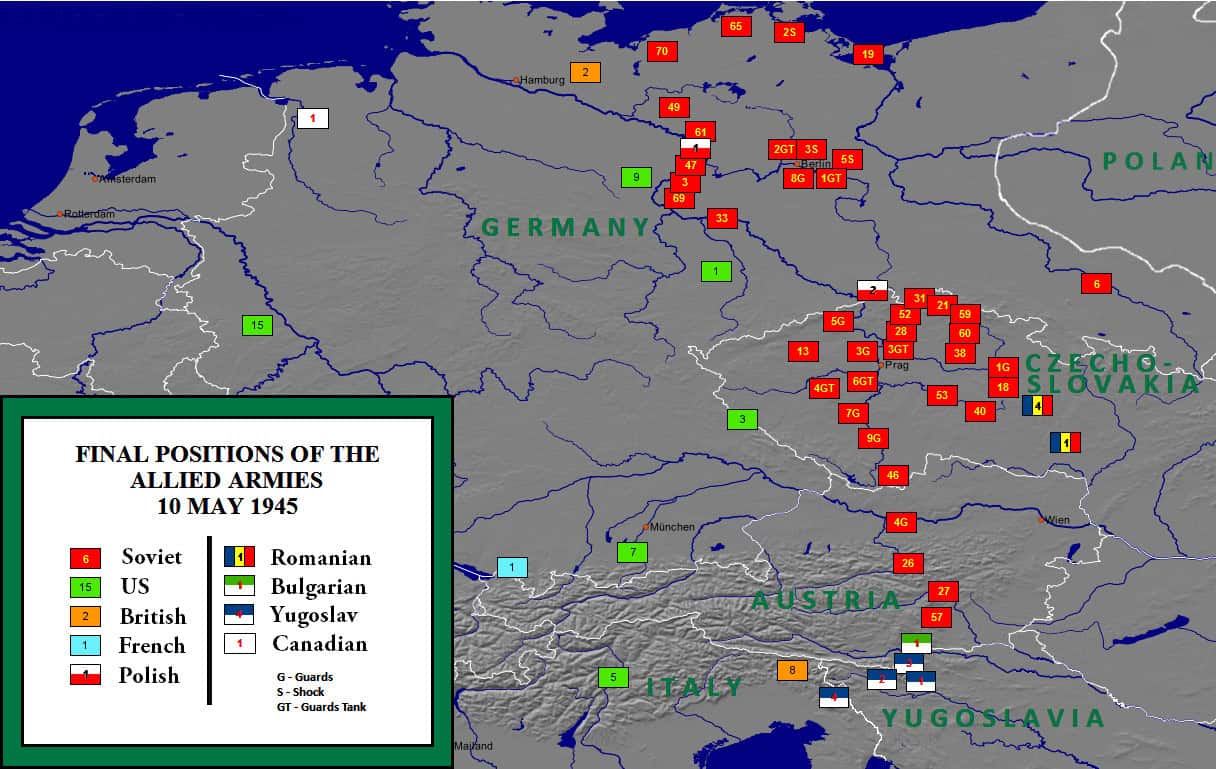

The Russian forces pushed from the eastern front while the other Allied armies pushed from the west, leading to the defeat of the German army. It's estimated that 29,000 Americans were killed during the storming of Normandy and another 106,000 were wounded or missing.

Question

What was the major battle fought between the United States and Japan in 1942?

Answer: The Battle of Midway

The Battle of Midway took place almost six months after the Japanese ambush on Pearl Harbor. Japan's goal was to remove the United States from the Pacific area so they could gain more power in the southwest Pacific islands and East Asia.

After days of fighting, United States troops forced the Japanese to retreat from the battle. Americans were prepared for the battle because they had learned how to break Japanese communication codes in 1942.

Question

What was the plan to help European countries improve economically after World War II?

Answer: The Marshall Plan

After the continent was ravaged by war, the rebuilding process began, with help from countries from all over the world. The Marshall Plan was created in 1947 by Secretary of State George Marshall and provided over $15 billion in aid to European countries over four years.

The Marshall Plan was designed to rebuild cities, industries, and infrastructure. This also helped the United States by removing trade barriers, fostering commerce between European countries, and providing a market for American goods to be sold.

Question

What policy was used to contain Communism after World War II?

Answer: Containment

The United States developed a strategic geopolitical foreign policy after the war to stop the spread of communism. Also known as the Truman Doctrine, it simply stated that the United States would provide economic, military, and political aid to democratic countries that were threatened by communist influences.

There are four parts to the policy of containment. First, block the Soviet Union's expansion of power. Second, expose Soviet pretensions. Third, retract the control and influence of the Kremlin. 4. Foster destruction within the Soviet Union

Question

What was the German Air Force called?

Answer: Luftwaffe

Luftwaffe was Germany's version of the Air Force and was tasked with defending Germany in all air matters. Created in 1935, the Luftwaffe was commonly believed to be the strongest air force in the world and it played a huge part in Germany's blitzkrieg battle tactics.

Over three million men served in paratrooper, air defense, and air force units from 1939 to 1945. The Allied forces disbanded the Luftwaffe after claiming victory in 1946.

Question

Which famous American general led troops in the Pacific?

Answer: General Douglas MacArthur

General MacArthur notably served in World War I, World War II, and the Korean War, and was one of the first servicemen to earn a five-star rank. He spent most of his life in the army and also served with the Phillippine Army as a field marshal.

He was given many military awards including the Army Medal of Honor, the Bronze Star Medal, the Korean Service Medal, and the American Defense Service Medal.

Question

Which battle was fought in North Africa and was a turning point for the Allies?

Answer: Second Battle of El Alamein

The battle was fought between the Axis Powers and the British Eighth Army and prevented the spread of them into Egypt. This kept the Allied forces in charge of the Suez Canal and blocked forces from moving their invasion into the Middle East.

Question

What was the point of the Tokyo War Crimes Trials?

Answer: To Hold Japanese Leaders Accountable

In their effort to expand and take power over much of the Pacific, Japanese leaders committed atrocious war crimes and were held accountable during the Tokyo War Crimes Trials. They lasted twice as long as the Nuremberg trials and were created in part by General MacArthur.

The trial went on for 2.5 years and had over 4,300 exhibits of evidence submitted. Some defendants were found mentally unfit for trial while others were sentenced to death. Others were sentenced to life in prison.

Question

Which part of the French government collaborated with Nazi Germany?

Answer: The Vichy Regime

After France was conquered, the Vichy regime succeeded the Third Republic for a good portion of World War II. Also known as the French state, it was headed by Marshal Philippe Petain, the President of the Council.

The Vichy Regime collaborated with Nazy Germany in performing raids to capture Jews and other people considered undesirable.

Question

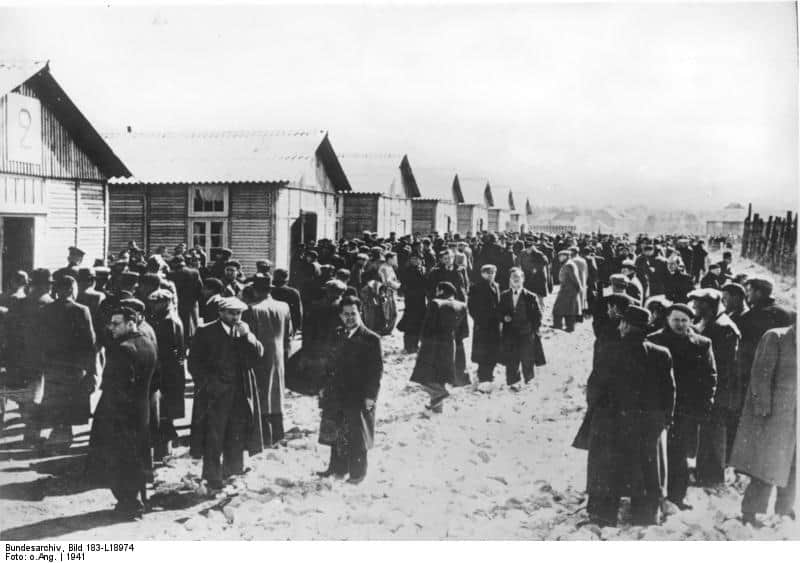

What did Nazi Germany call their plan to exterminate Jews?

Answer: The Final Solution

Nazi Germany's leaders used the term "Final Solution of the Jewish Question" to speak of the mass murder of the Jewish people. Rather than encouraging Jewish people to leave Germany and move to other parts of Europe, it became a systematic annihilation.

Nazi leaders anticipated removing 11 million Jews from the heart as part of the "Final Solution" and succeeded in murdering six million. This was the final stage of the Holocaust.

Question

When did the Germans invade the Soviet Union?

Answer:

Germans invaded the Soviet Union in 1941 with Operation Barbarossa. This was history's largest military ground invasion at the time, with thousands of aircraft and tanks, half a million horses, and almost four million troops involved. They advanced from the Gulf of Finland to the Black Sea across all of Eastern Europe.

Despite their efforts, German troops were unable to defeat Soviet forces, which was a crucial turning point. Russian troops were better prepared to fight in the rough weather conditions, but many German troops froze to death in the harsh winter of Russia.